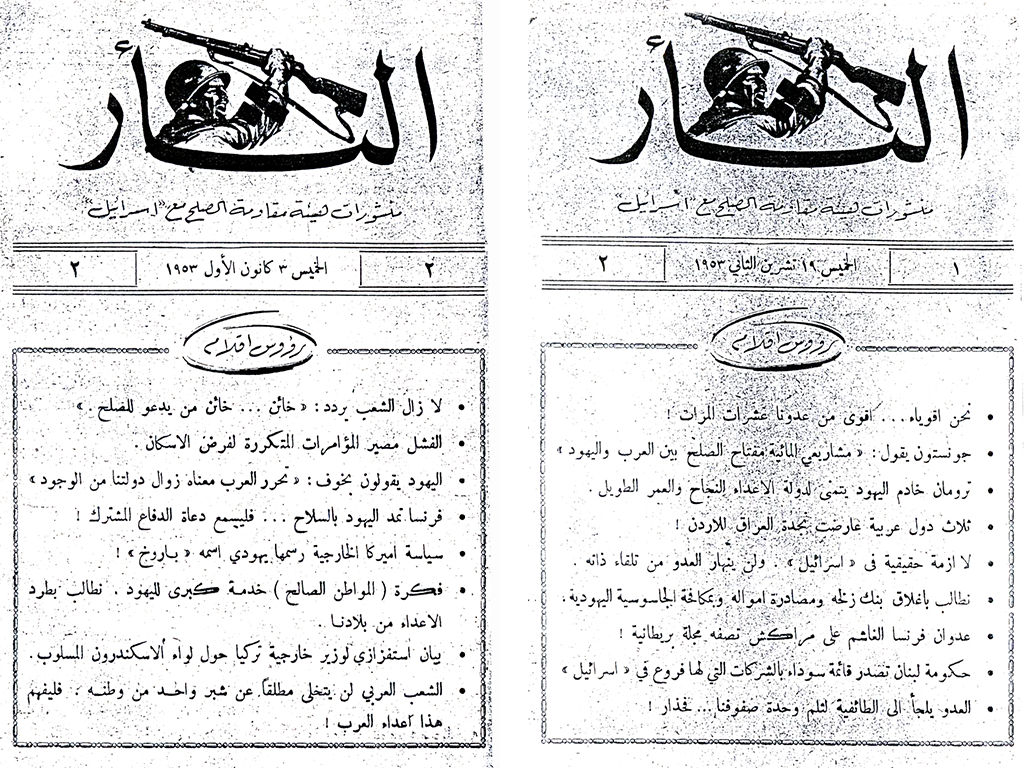

Soon after the Nakba revolutionaries began to formulate ideas analysing the cataclysmic event the Palestinians had experienced, and articulating a vision of how to respond to their national crisis. These ideas were spread through periodicals such as the Arab Nationalist Youth’s Al-Tha’r. These publications, often banned, were produced inexpensively by volunteers who were working underground. Still, they were enormously influential in Palestinian gatherings such as the refugee camps, helping to mobilise cadres into the ranks of revolutionary parties.

The early development of movements was often connected to these publications. For instance, Fateh in its earliest years became closely identified with Filastinuna, a journal that was founded in 1959.

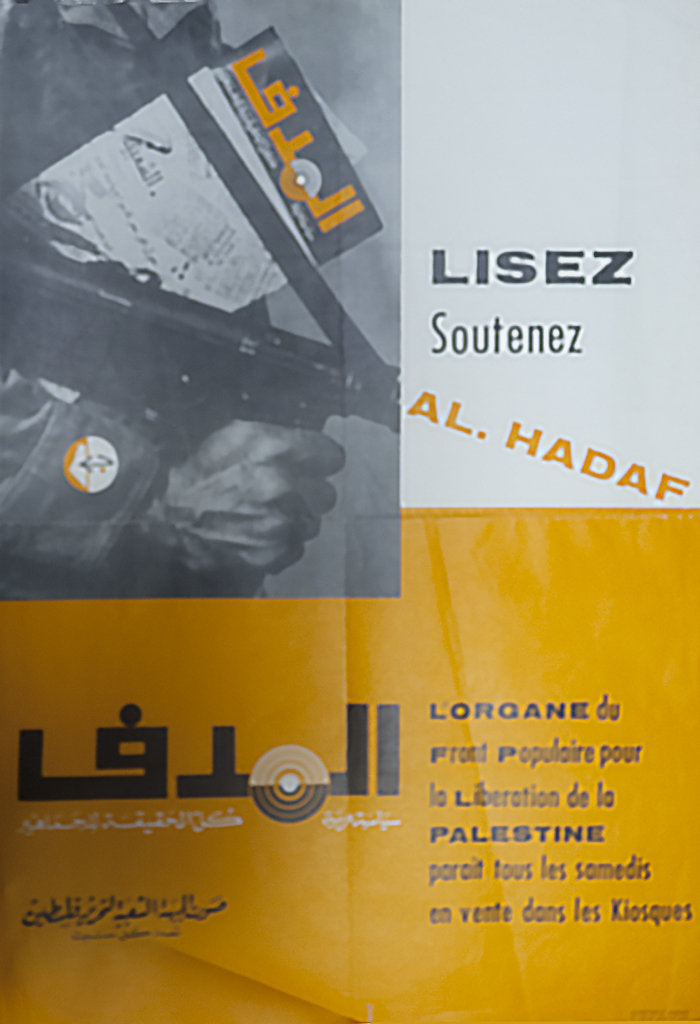

In the 1960s, revolutionary movements began to dedicate resources towards creating more professionally produced newspapers and magazines, such as the Movement of Arab Nationalists’ Al-Hurriya. Such publications disseminated revolutionary analyses, pieces of journalism, as well as cultural critiques. They also acted as vehicles for spreading internationalist and anti-colonial radical themes. In this regard, as much attention was paid to the images that were used as to the articles’ substance.

In the 1970s, non-partisan radical newspapers aligned to the revolution also began to proliferate, such as Beirut’s Al-Safir.

At the height of the radio age, the Palestinian revolution began to focus on using the airwaves for disseminating revolutionary consciousness, establishing the Sawt al-Thawra station. Revolutionary sensibility, as well as revolutionary ideas, were communicated through the broadcasting of songs.

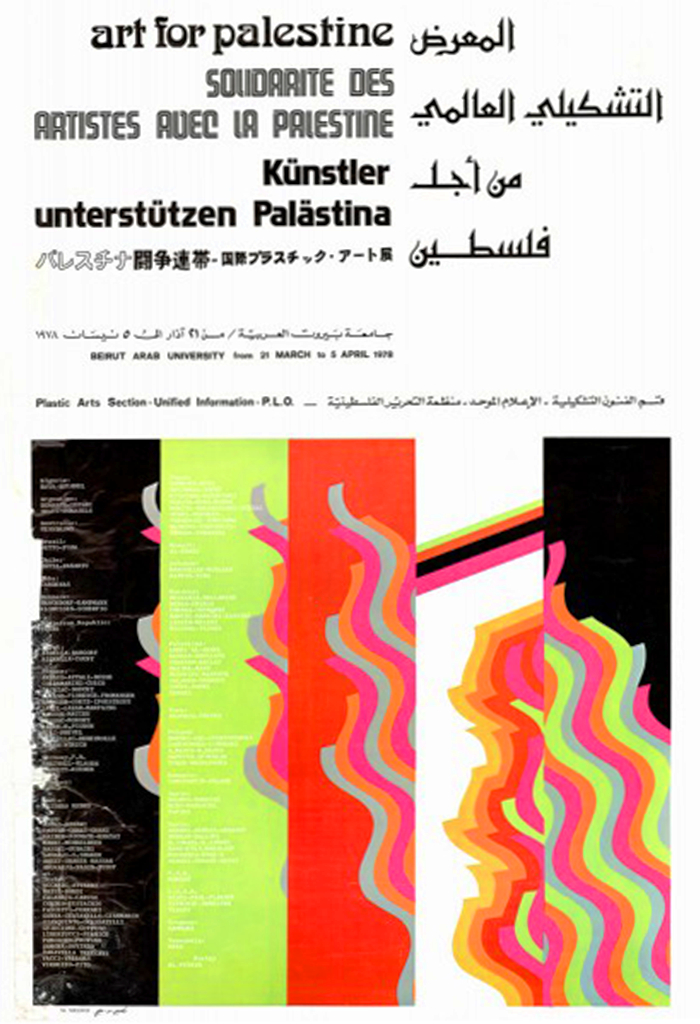

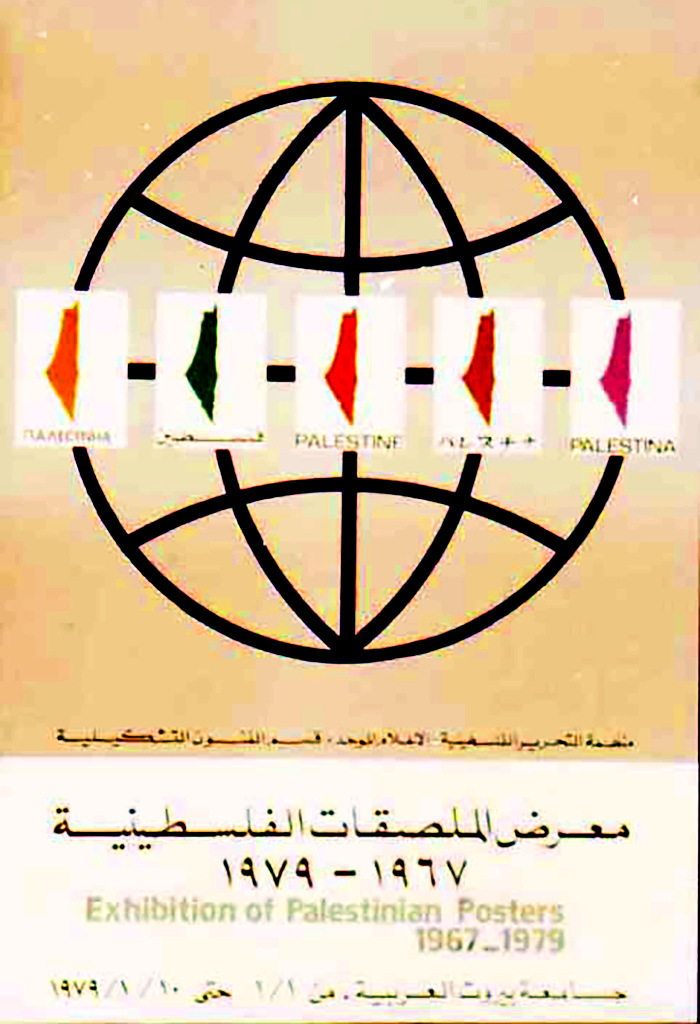

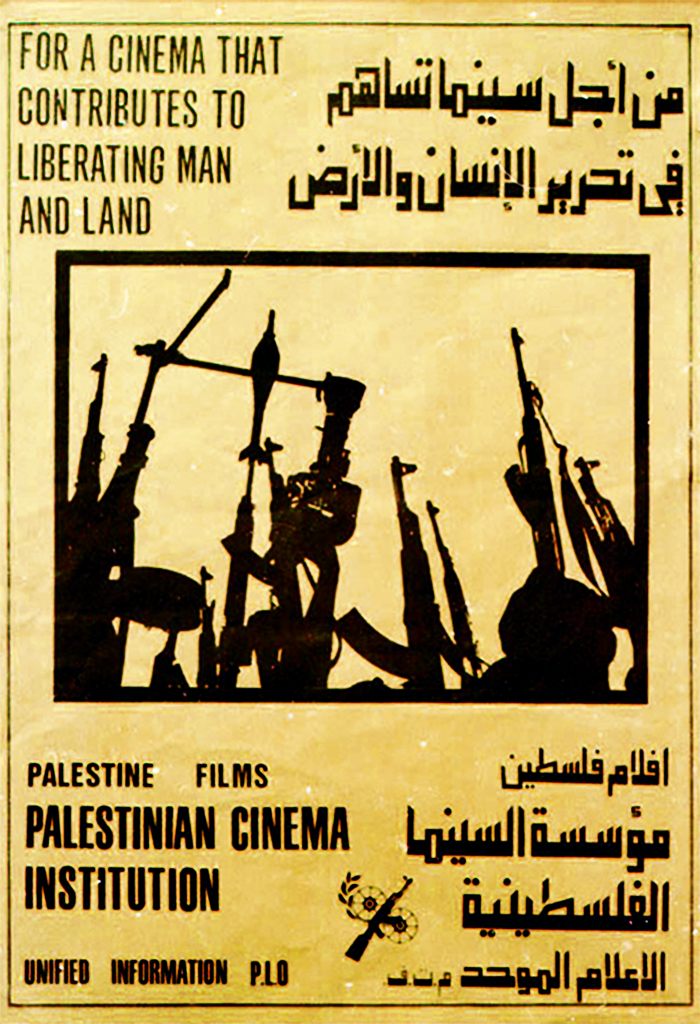

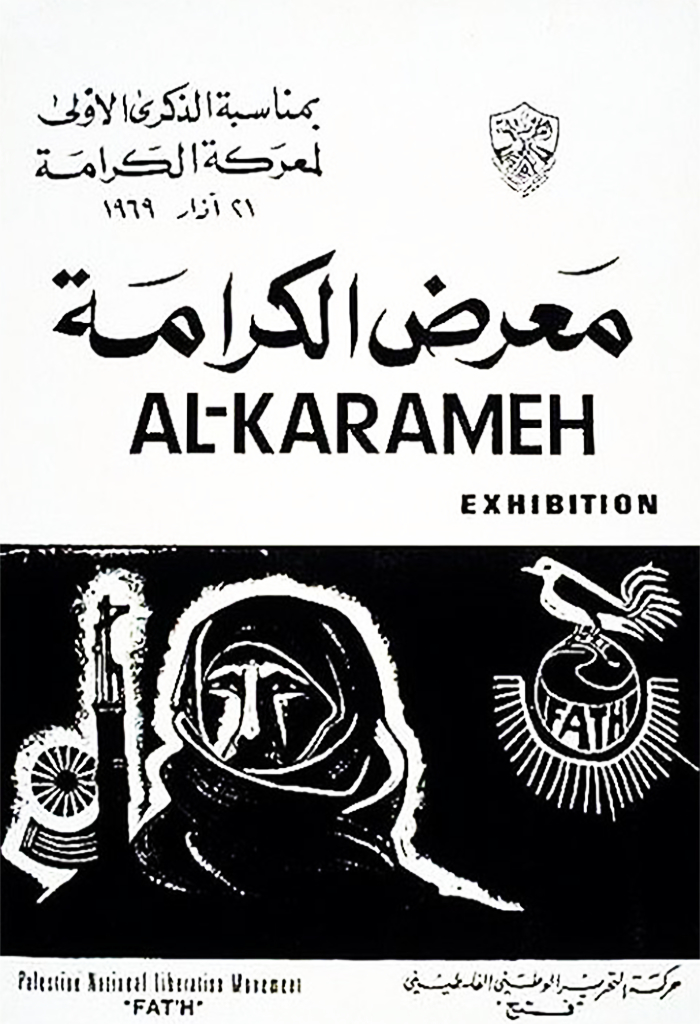

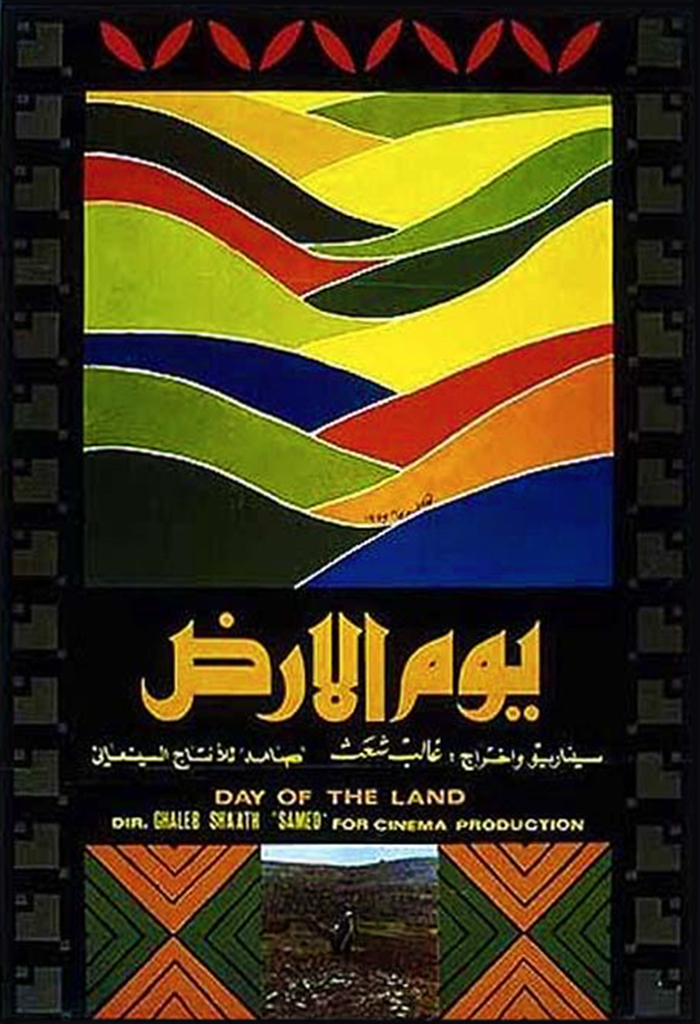

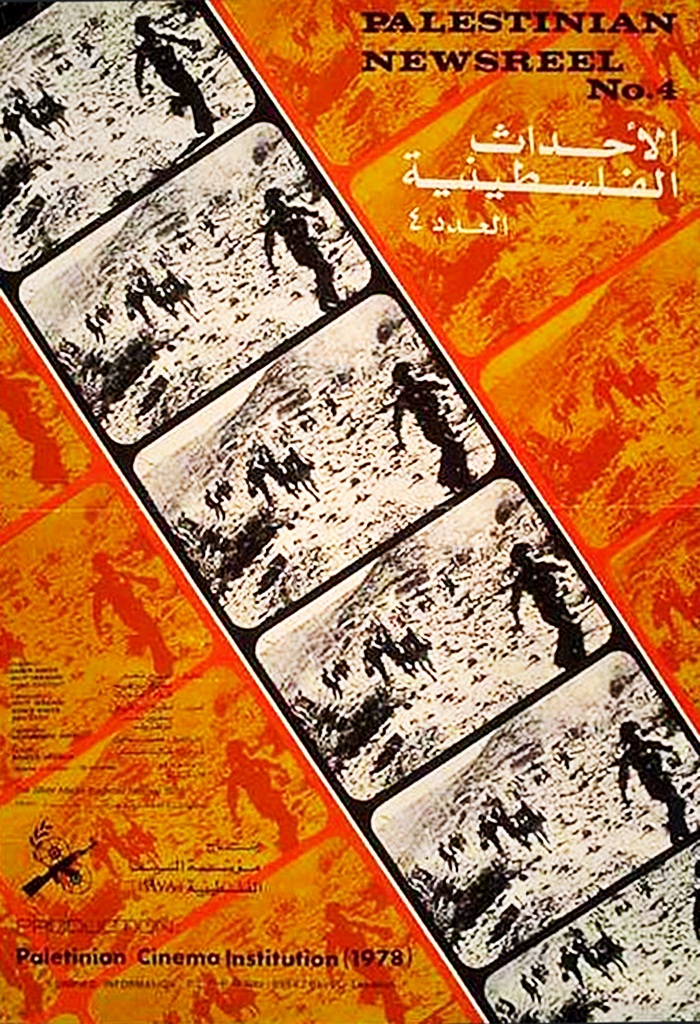

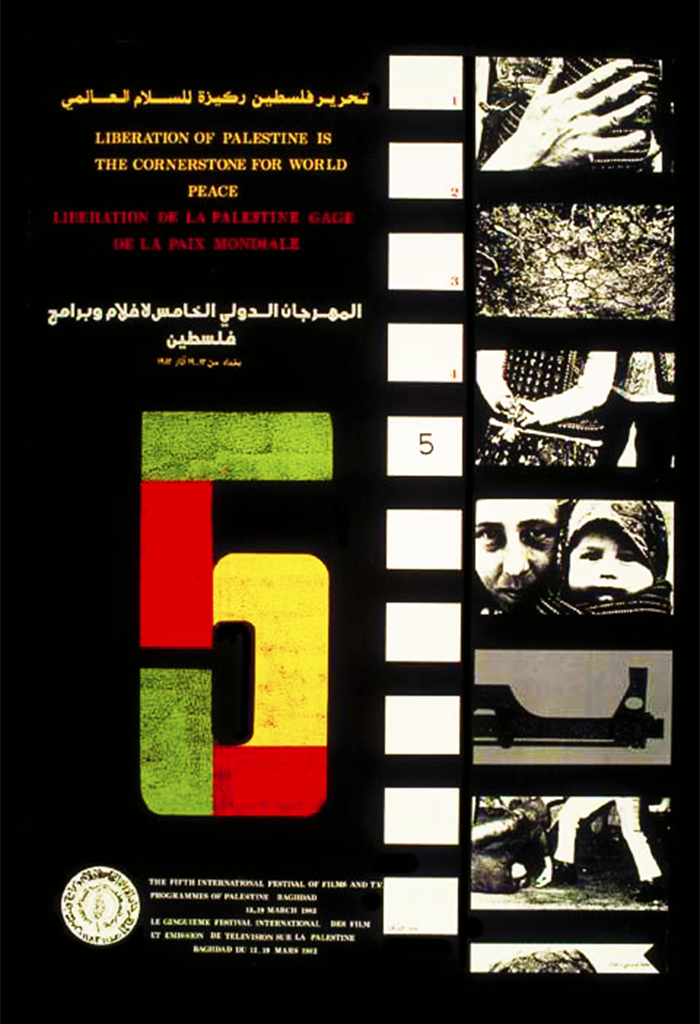

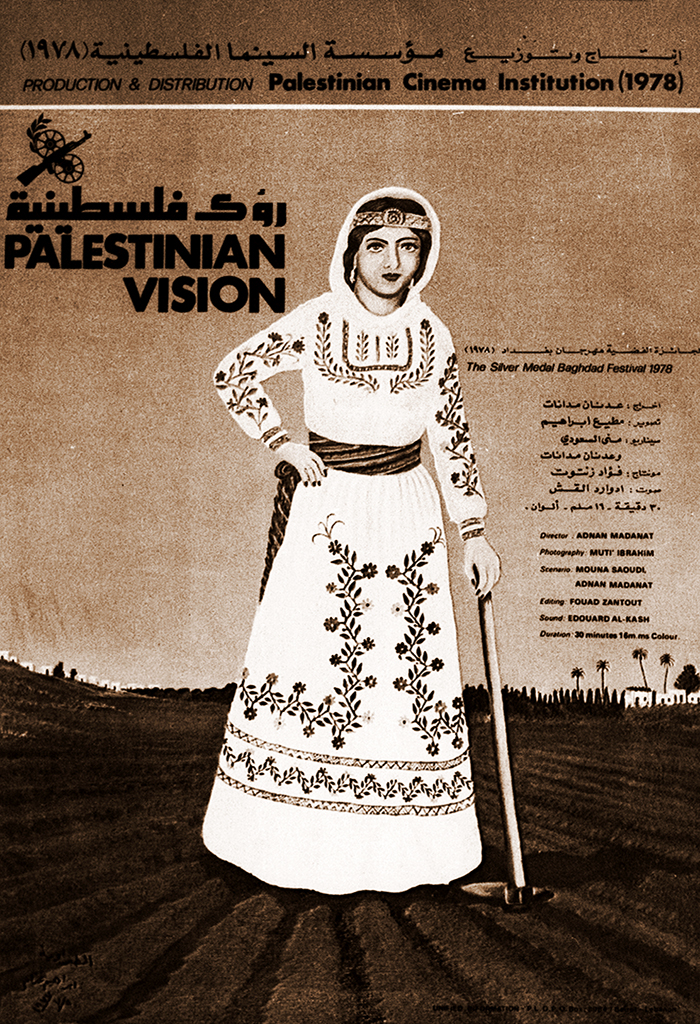

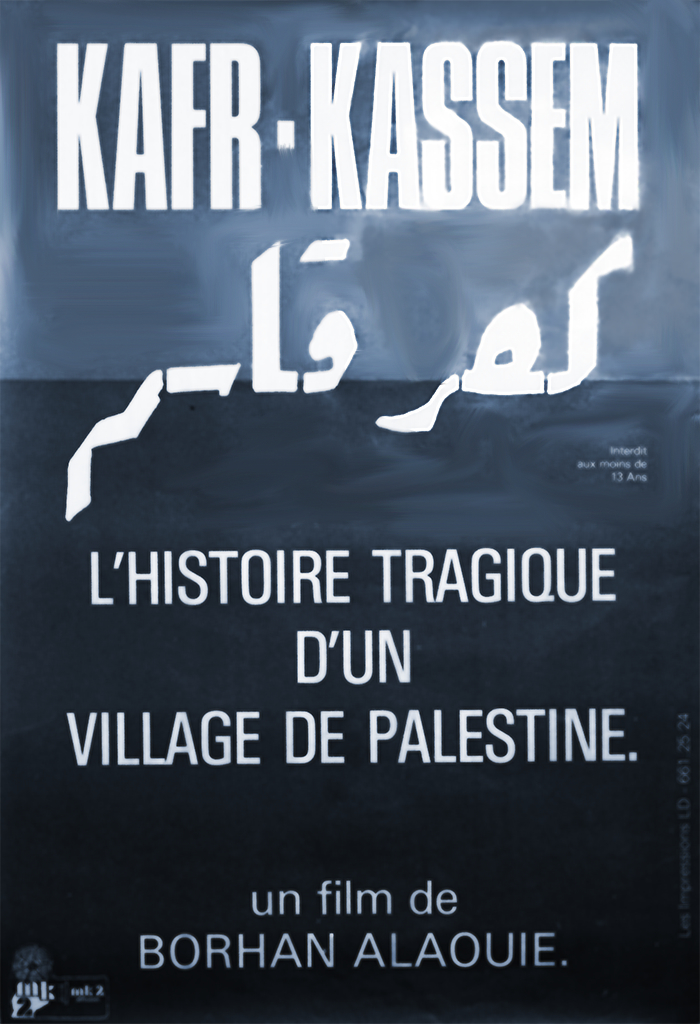

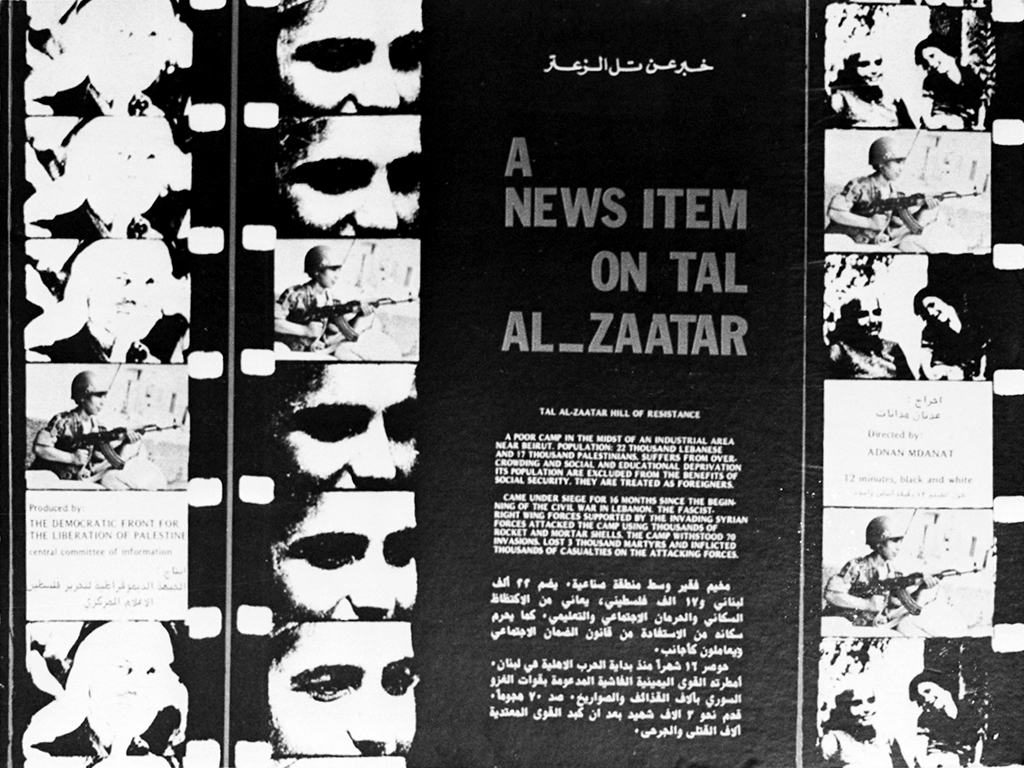

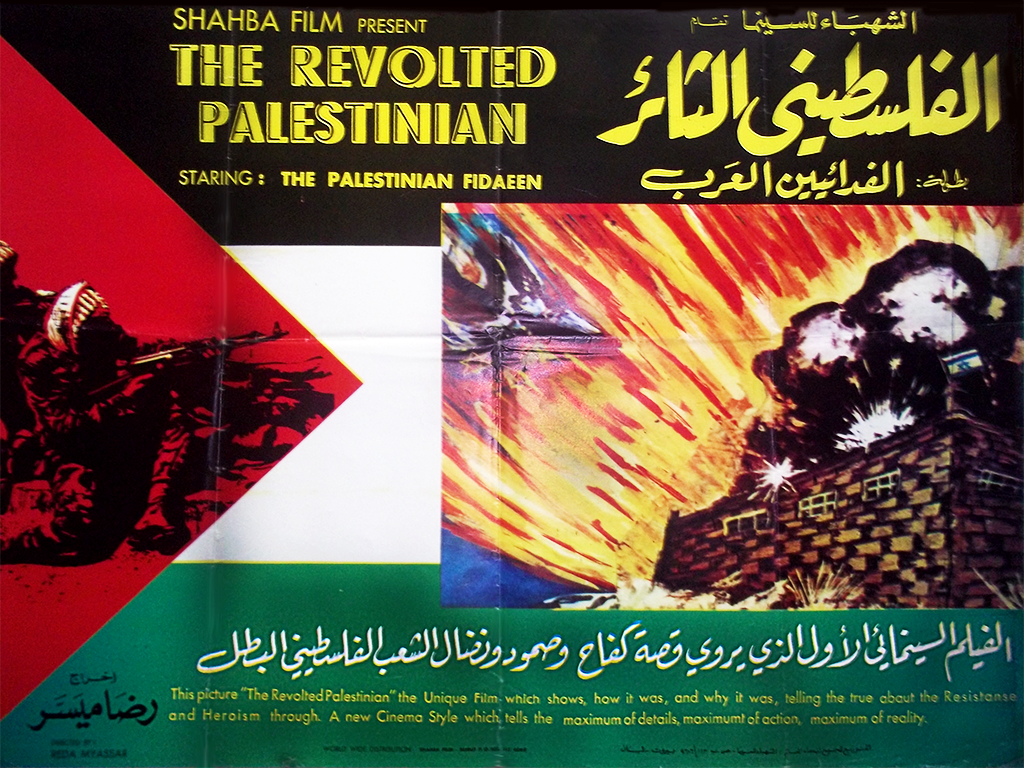

The Palestinian revolution gave birth to one of the most flourishing poster art traditions in the anti-colonial world, producing thousands of images that contained political, commemorative, and intellectual themes. A growing number of films also began to appear. Palestinian filmmakers and cameramen were sent on scholarships to study abroad, especially in the socialist countries. Revolutionary international and Arab artists also contributed to Palestinian film efforts, joining the PLO’s film unit.

The revolution disseminated traditional forms of cultural production such as embroidery. Such old crafts acquired a new meaning that transcended the original use value of their products. In a context in which there was so much pressure to erase Palestinian identity, traditional crafts asserted the continued connection between Palestinians and their older cultural traditions. At the same time, they provided an avenue of economic production and financial self-sufficiency for women in the refugee camps.

The Palestinian revolution also opened avenues for spreading experimental cultural production, through institutions such as the PLO’s Plastic Arts Union.

The ideas of the Palestinian revolution spread right across the anti-colonial world, significantly influencing revolutionary activity across Latin America, Africa, and Asia. On a personal level, they transformed the lives of radical filmakers, artists and writers, such as Jean Luc Godard, artist Claude Lazare, and writers James Baldwin and Jean Genet, along with radical international symbols such as the Black Panthers, Malcolm X, and Mohammad Ali.