As the Palestinian revolution was launched by refugees exiled from their country, many of the revolution’s most defining moments took place outside the boundaries of historic Palestine. There were moments of great political contestation, such as the 1955 demonstrations in Jordan against the Baghdad pact, where Palestinians contributed to challenging colonial structures in the Arab world.

Some moments were foundational in nature, witnessing the birth of major political structures. One example is the great flurry of political organising across Palestinian communities worldwide in that culminated with the establishment of the PLO in 1964.

A few historic moments can be seen as transitional in nature, marking the movement from one era to the next. For instance, the 1968 battle of Karameh almost immediately came to symbolise the transition from dependence on the classical armies of Arab states, to a strategy focused on developing a collective Palestinian capacity for people’s war. In the immediate aftermath of the battle, enlistment in the armed struggle increased exponentially, with adhesions from thousands of young Palestinians, Arabs, and international supporters from across the world.

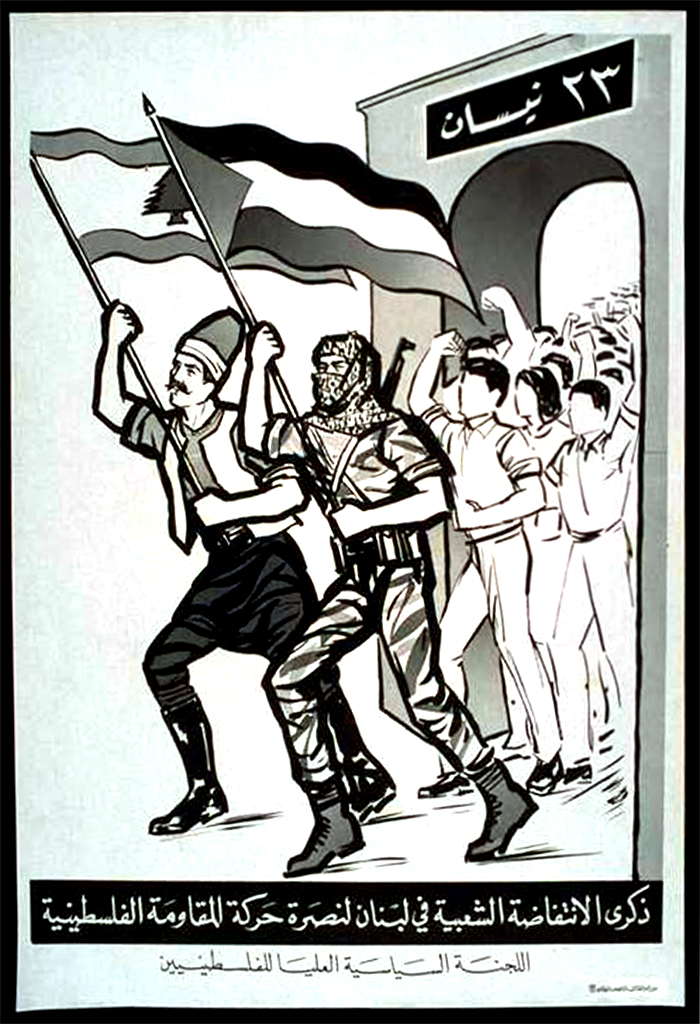

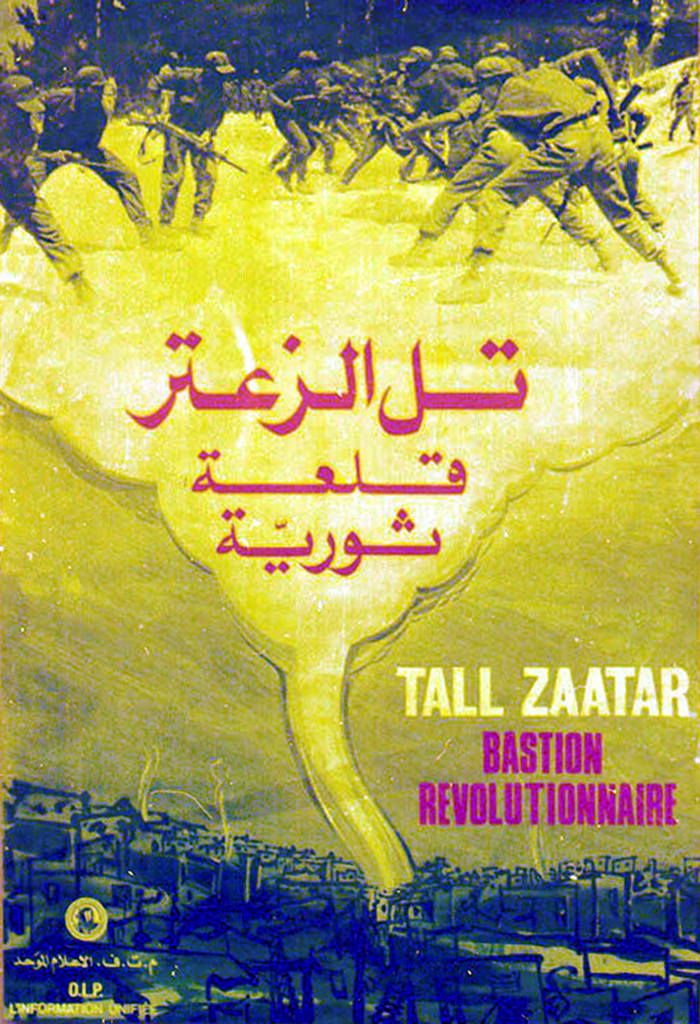

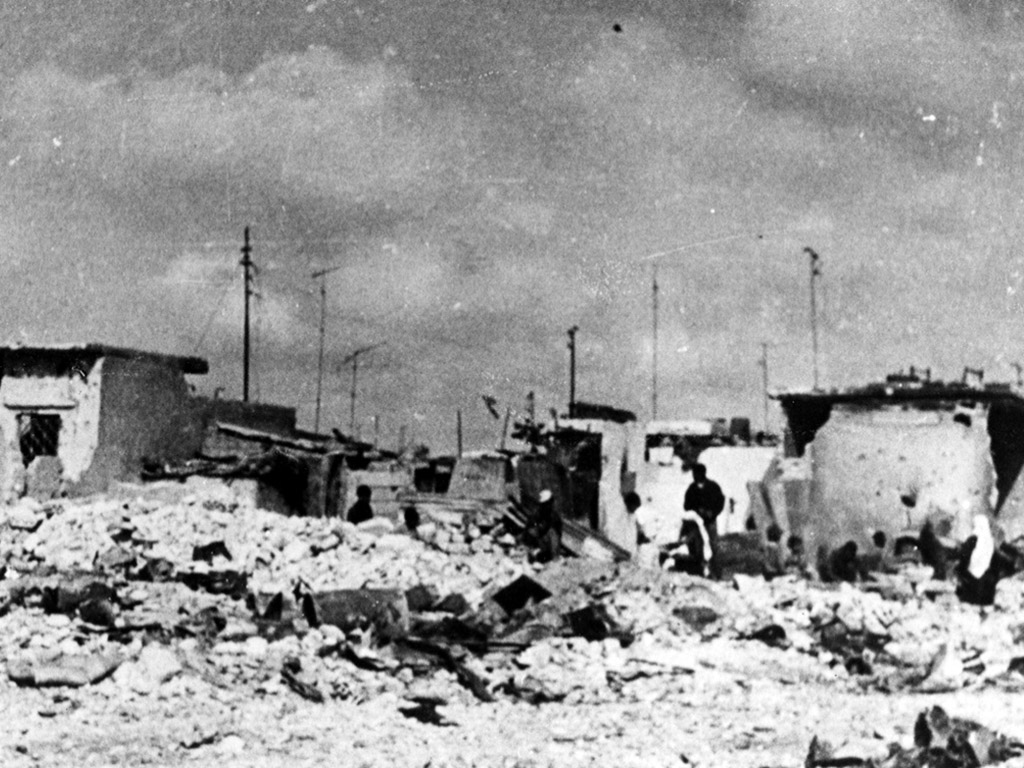

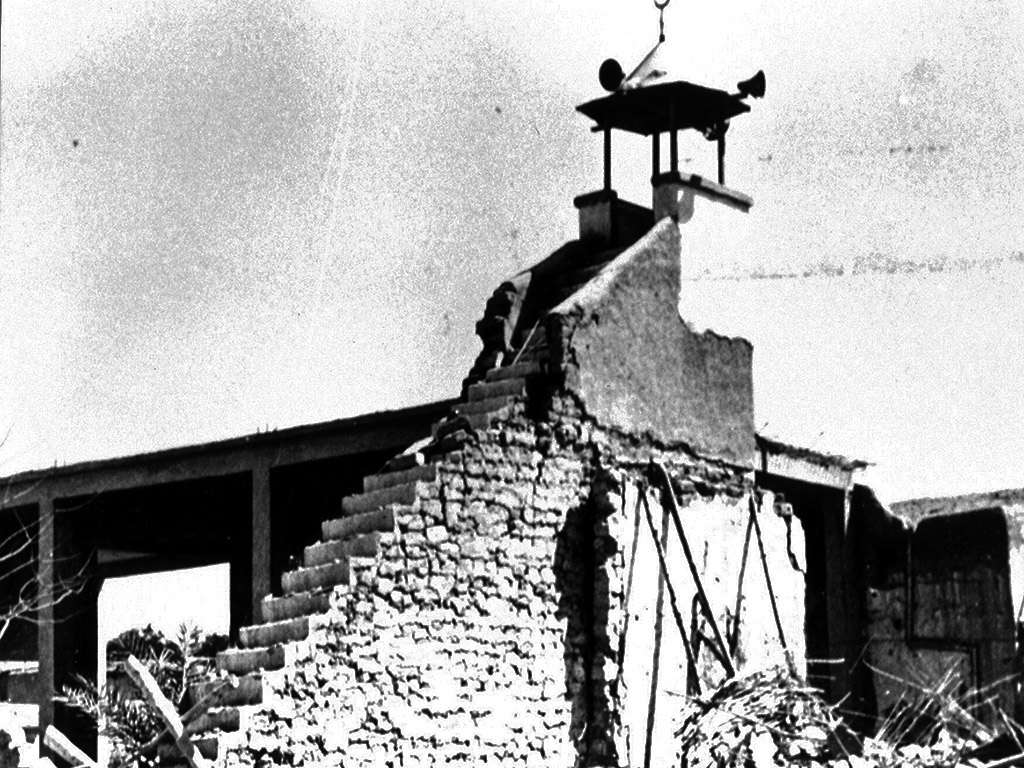

For a refugee people, suffering the oppressions of stateless exile, there were several profound moments of emancipation. One of these was the liberation of the Palestinian refugee camps in Lebanon in 1969, which saw the overthrow of the suffocating control of the 2nd Bureau security forces. During this moment, Palestinian civic institutions of the revolution developed their own community governance capacity across the multitide of refugee camps in Lebanon.

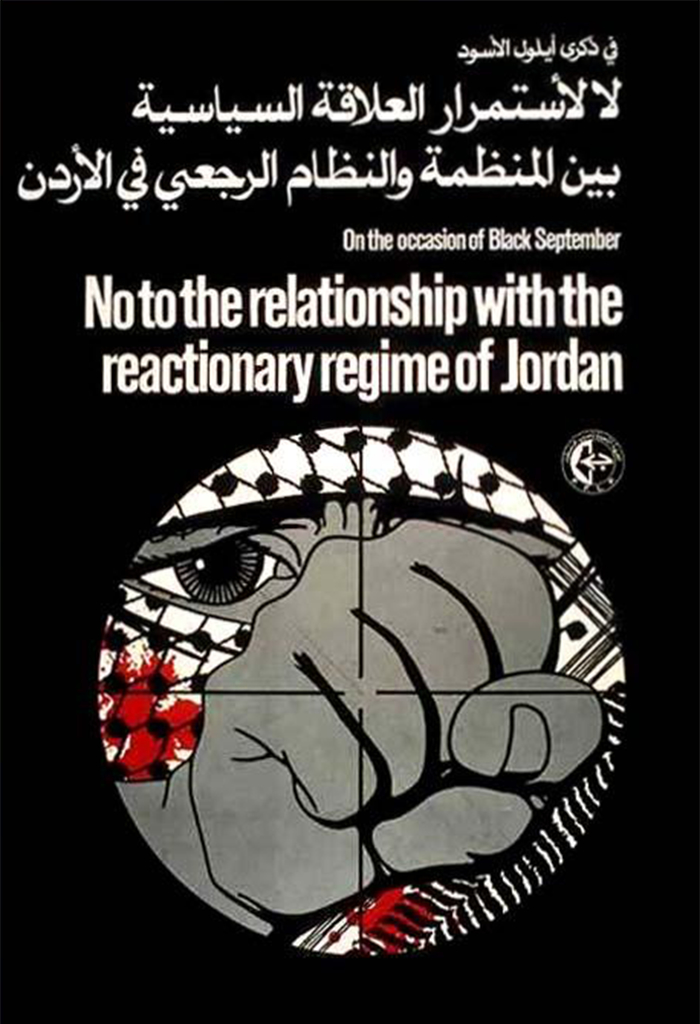

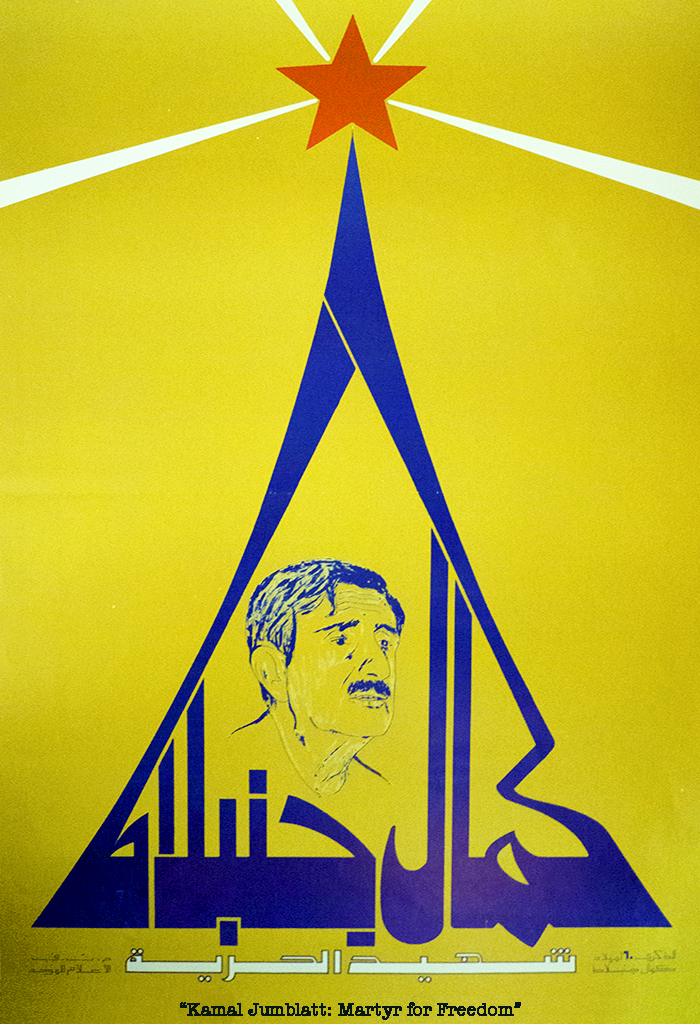

In asymmetrical anti-colonial struggles, such as the Palestinian one, major national setbacks occur regularly, and give rise to moments whose nature is contested both inside and outside the revolution. One of the foremost examples here is Black September 1970 and its aftermath in Jordan, which saw the expulsion of Palestinian forces from the country. The event, as presented by Jordanian monarchical authorities, contrasted widely with Palestinian popular accounts. It also led to widely varying assessments and auto-critiques within the Palestinian revolution itself. Whichever way it is analysed, this watershed moment was accompanied by enormous suffering, and the loss of one of the most important sites of Palestinian resistance.

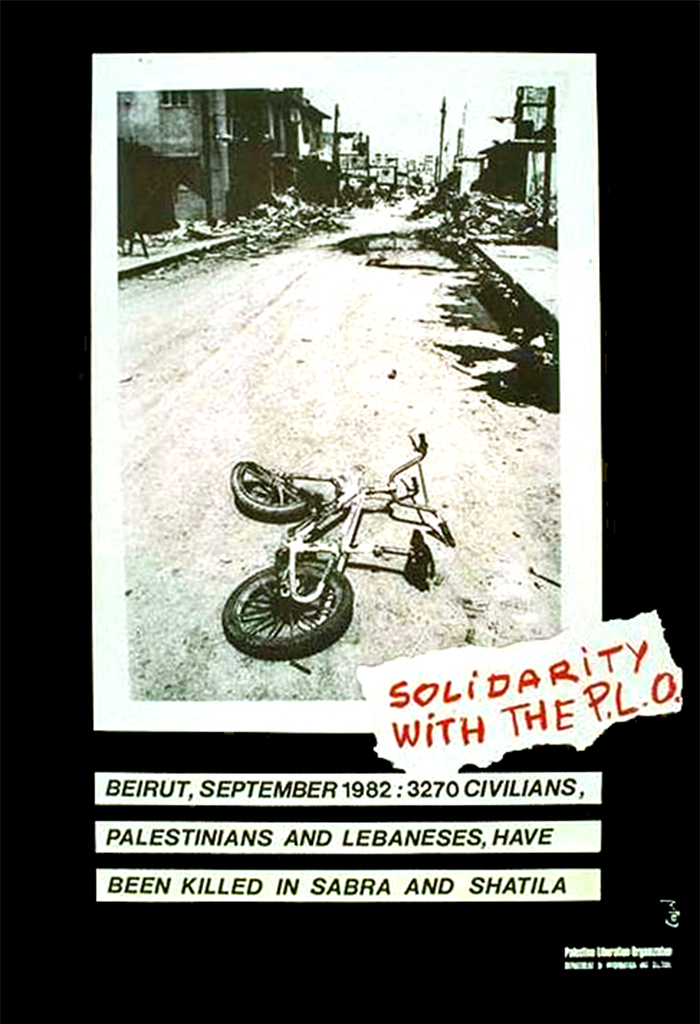

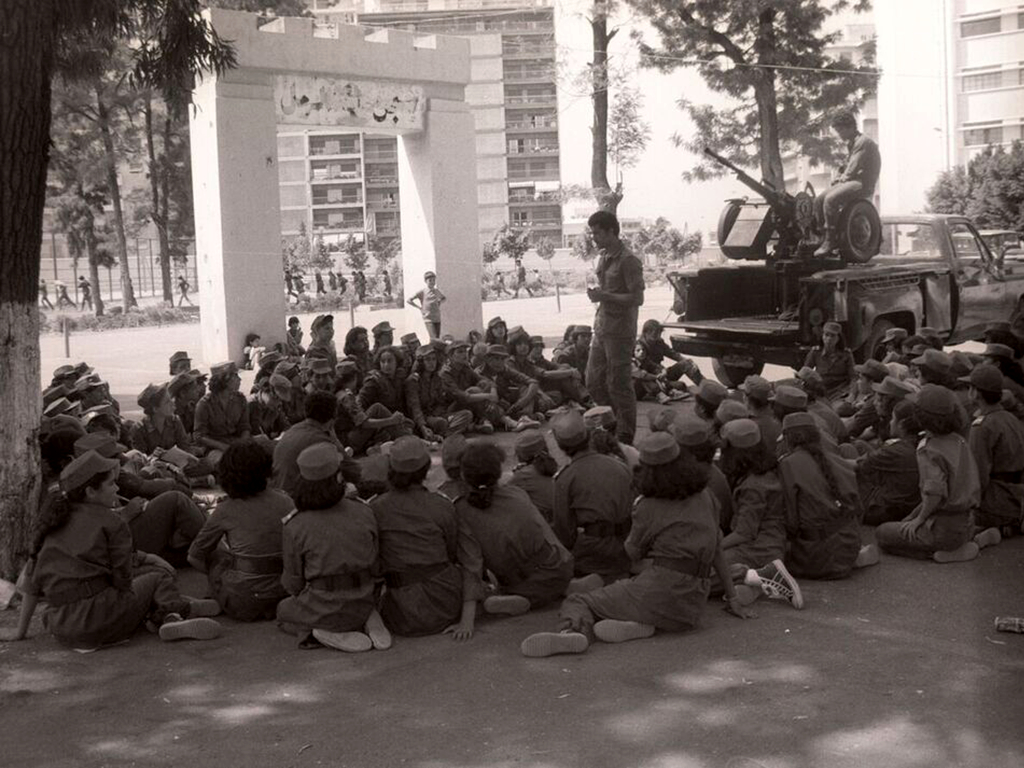

Some moments were widely anticipated before they occurred, resulting in extensive preparation. One example here is the general mobilisation announced in the run up to the June 1982 Israeli invasion of Lebanon. Men and women were given military training and emergency plans were put in place, Palestinian university students on scholarships across the world made their way back to defend their people, and popular camp committees, as well as the staff of the Palestinian Red Crescent hospitals and clinics, prepared emergency plans.

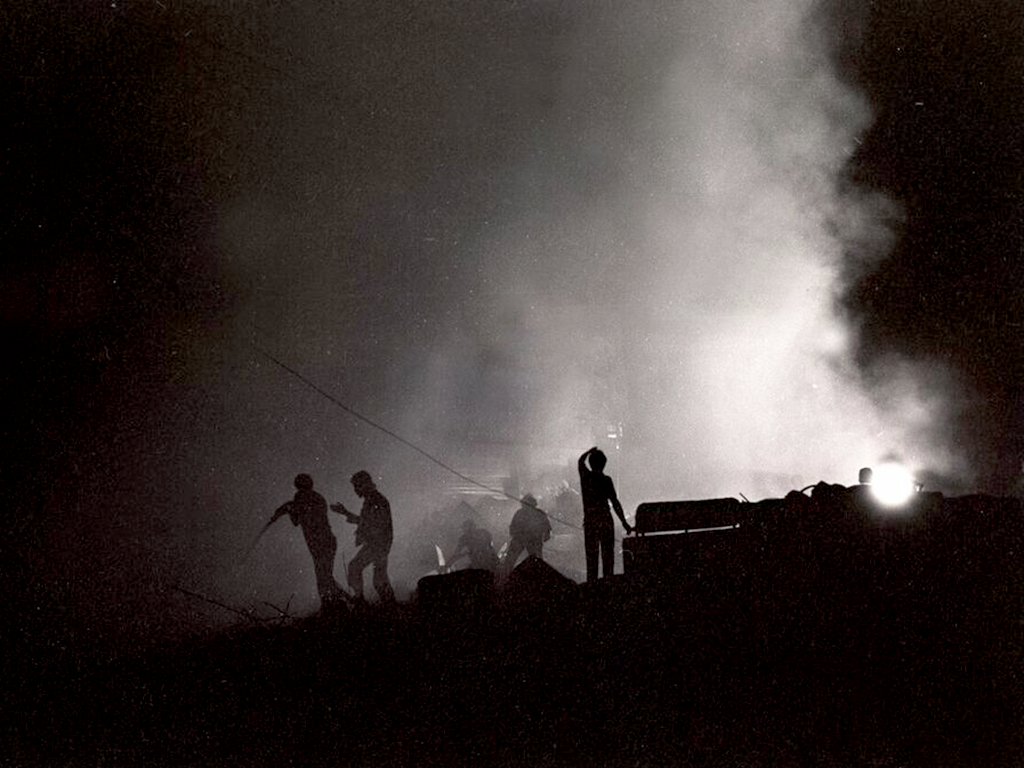

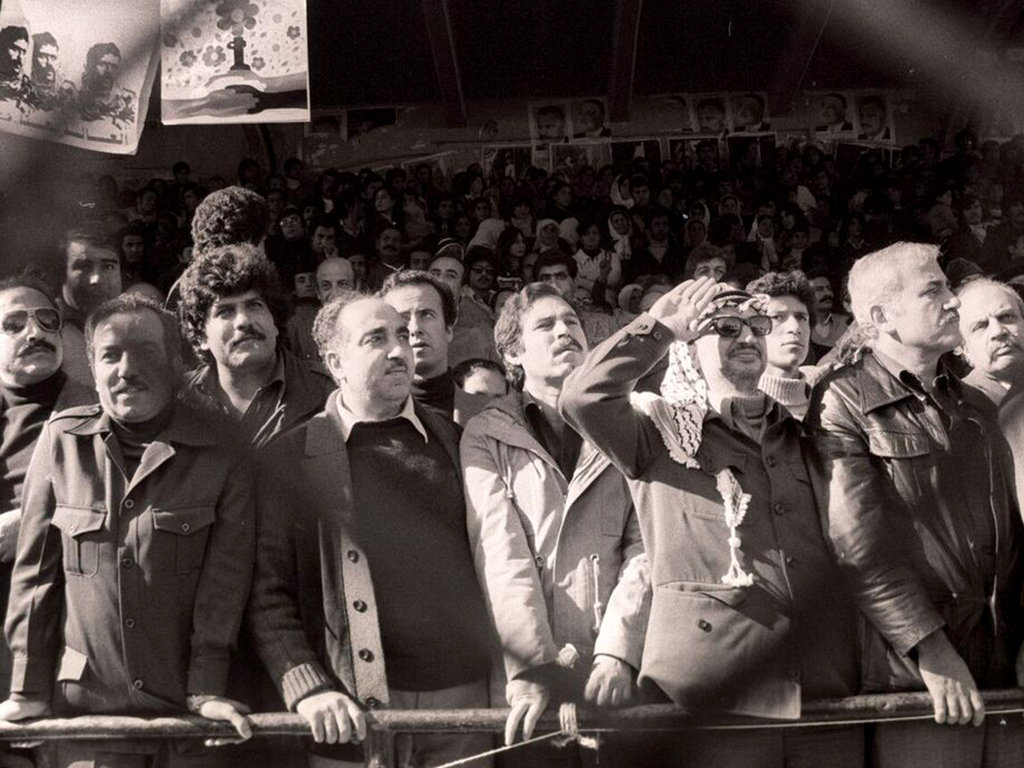

Major terms in the Palestinian political lexicon, such as that of Sumoud (steadfastness), became synonymous with certain moments, such as the 1982 siege of Beirut. Despite an initial military collapse in the South of Lebanon, Palestinian and Lebanese National Movement forces were able to consolidate their presence in the capital of Beirut, with the entire revolutionary political, military, social, and cultural infrastructure operating effectively together. This allowed the revolution to withstand the Israeli siege for two months, before withdrawing under the pressure of thousands of civilian casualties caused by Israeli carpet bombing of residential areas .

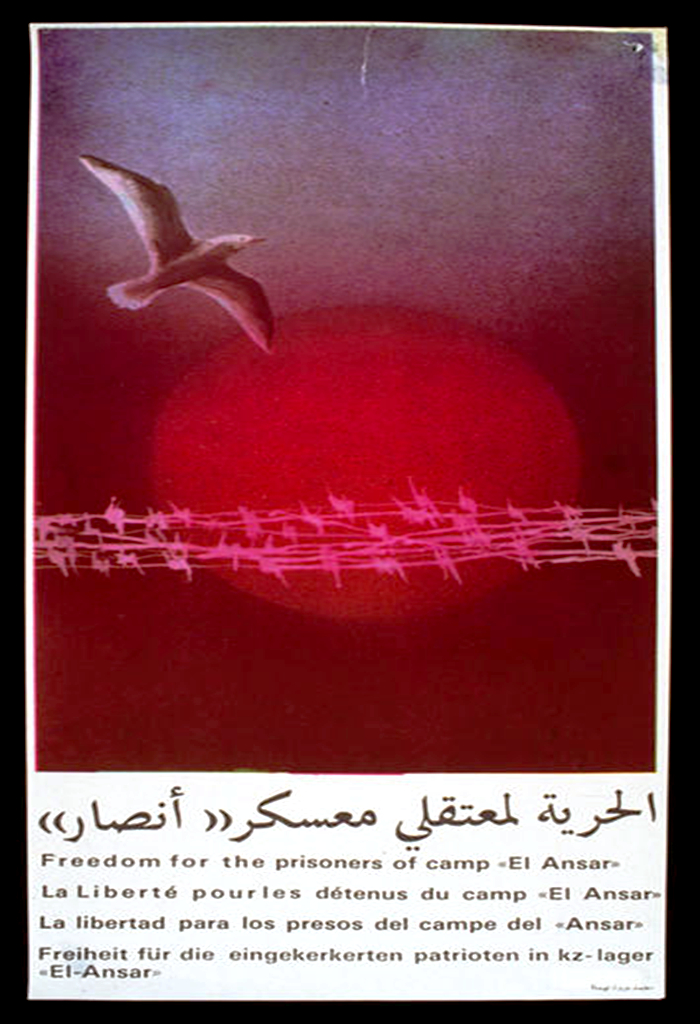

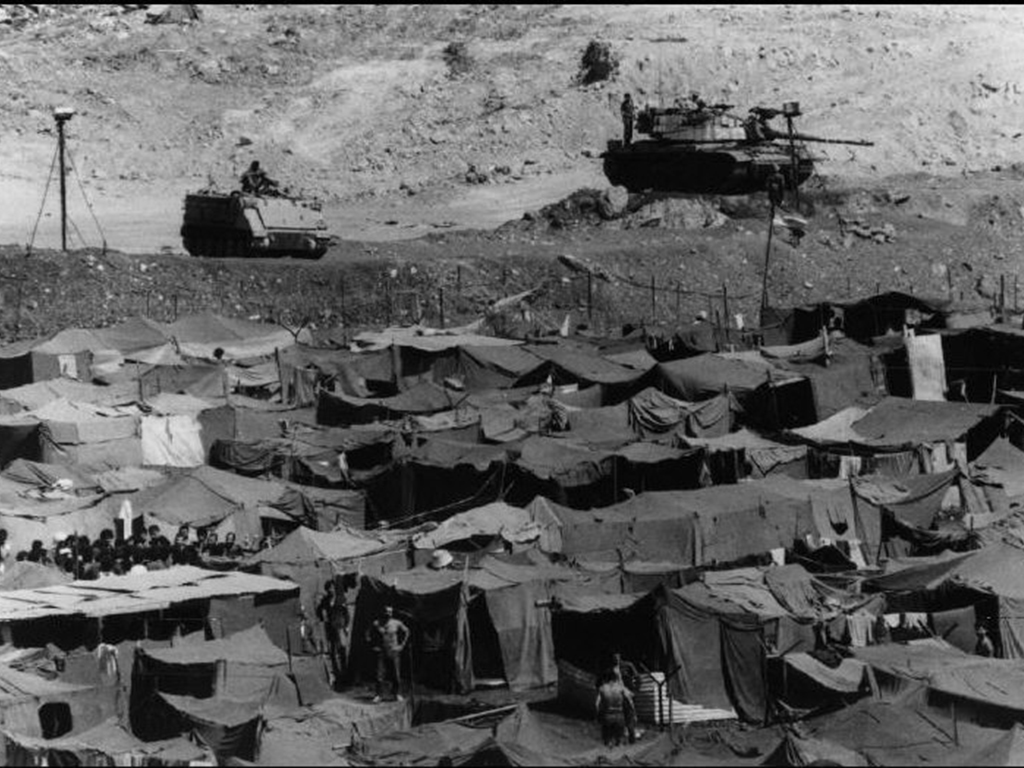

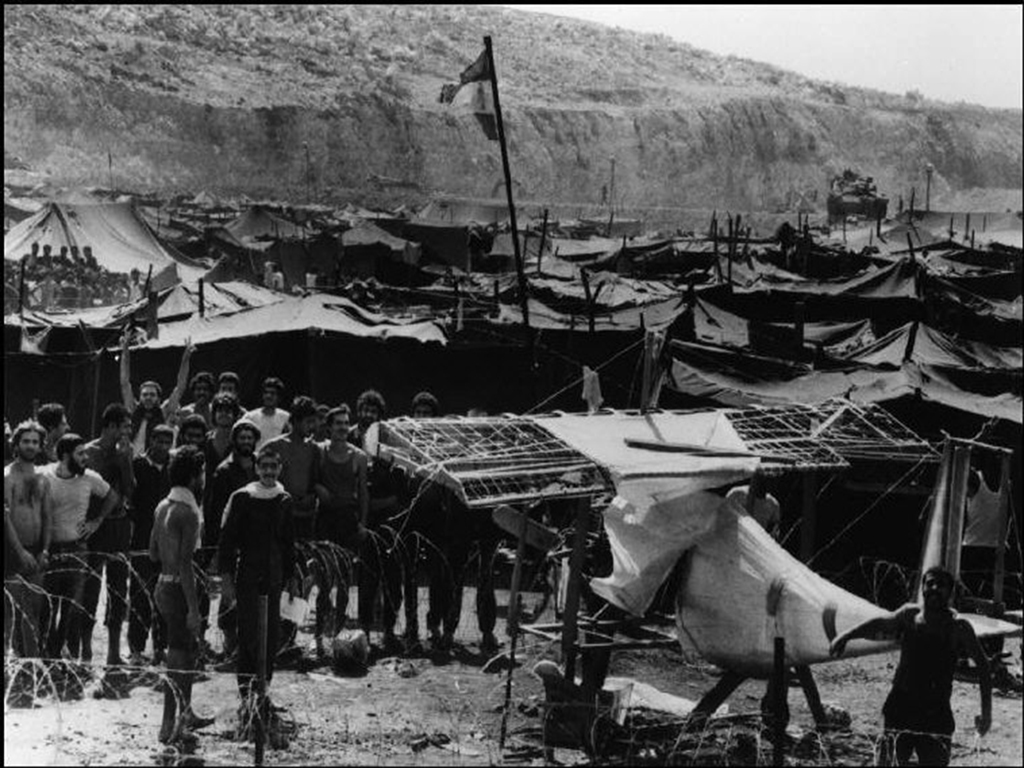

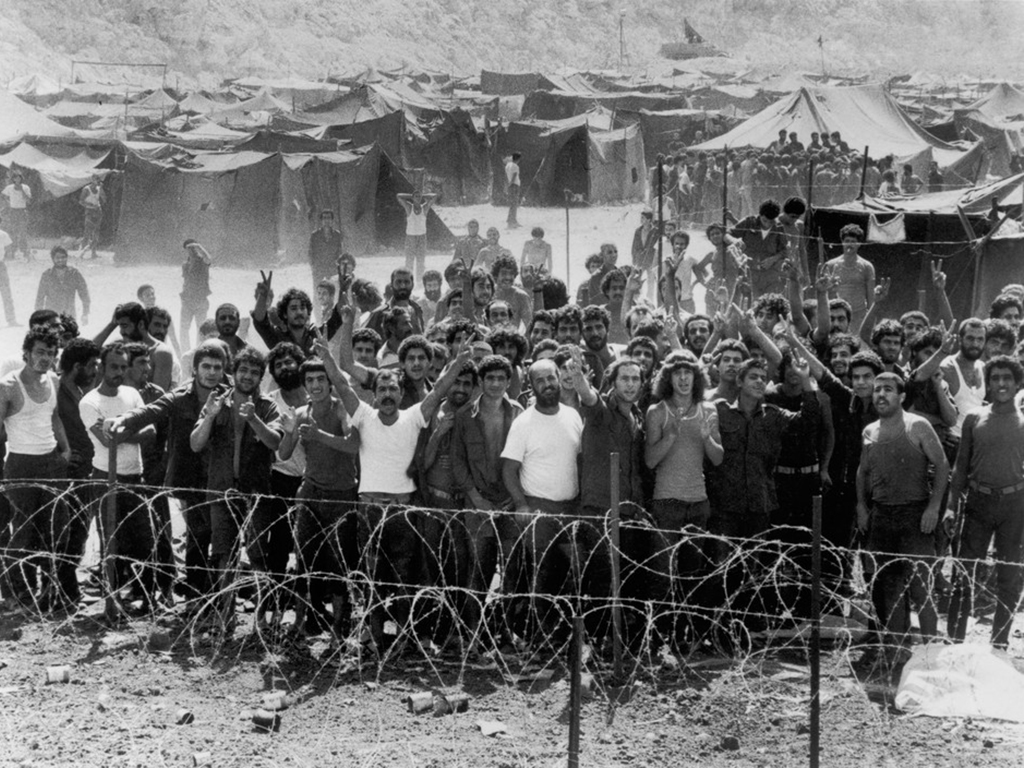

As was the case inside Palestine, some major national moments outside Palestine emanated from inside the prisons. This included the concerted political mobilisation by the prisoners at Ansar, a prison camp created by Israeli military authorities, after the start of the 1982 invasion.