Palestinian revolutionary mobilisation was shaped by the direct experience of the Nakba. Palestinians saw the destruction of their society, and many of them were suddenly experiencing life as refugees living in makeshift tents, prevented from returning to their homes. This collective trauma was powerfully expressed in the poetry, popular songs, and paintings of the period. The shock extended beyond Palestinian circles, and the dramatic shift was strongly felt in neighbouring countries. This had an immediate impact on the political consciousness of Arab revolutionary adults and it also became a formative childhood memory for future Arab cadres.

This catastrophic situation prompted Palestinians to address their most urgent and basic human needs: a return to their land, and its liberation from a newly established settler-colonial system that excluded them, the native population, from it. The earliest mass popular mobilisations in the first half of the 1950s took place around these two key imperatives, which were gradually transformed into more axiomatic demands and principles. During these mobilisations, carried out by grassroots activists in coordination with the camp elders, Palestinian refugees expressed their rejection of any attempt permanently to re-settle them in the host countries of their exile.

Mobilisation took different guises. For instance, in the 1950s, the rapid dispossession of the Palestinian people was widely analysed as resulting from the lack of military knowledge and equipment needed for self-defense. Accordingly, there were mass campaigns calling on Arab states to provide military training to Palestinians. In Syria, popular mobilisation on this issue was highly successful, resulting in a presidential decision introducing mandatory military service for Palestinians. In Gaza, popular mobilisation demanding the training of Palestinians was also successful, especially in the aftermath of the Israeli raids of 1954.

Mobilisation was carried out at many levels and drew from many sources. Much of popular political activity in 1950s Cairo was carried out by Palestinian university student leaders. During the same period in Jordan, students played an important role, and were often encouraged to take political action by their teachers.

Mobilisation was intrinsically linked with the process of organisation, which was reflected in the founding and joining of movement and parties. However, there was a distinction between the two processes of mobilisation and organisation. When organised movements mobilised around an issue, they appealed beyond their individual ranks, aiming for the participation of the largest number of people possible. On most occasions, mass mobilisation took place when multiple groups and formations came together on a unified popular demand, as was the case for example in the demonstrations which took place against the Baghdad Pact in Jordan in 1955.

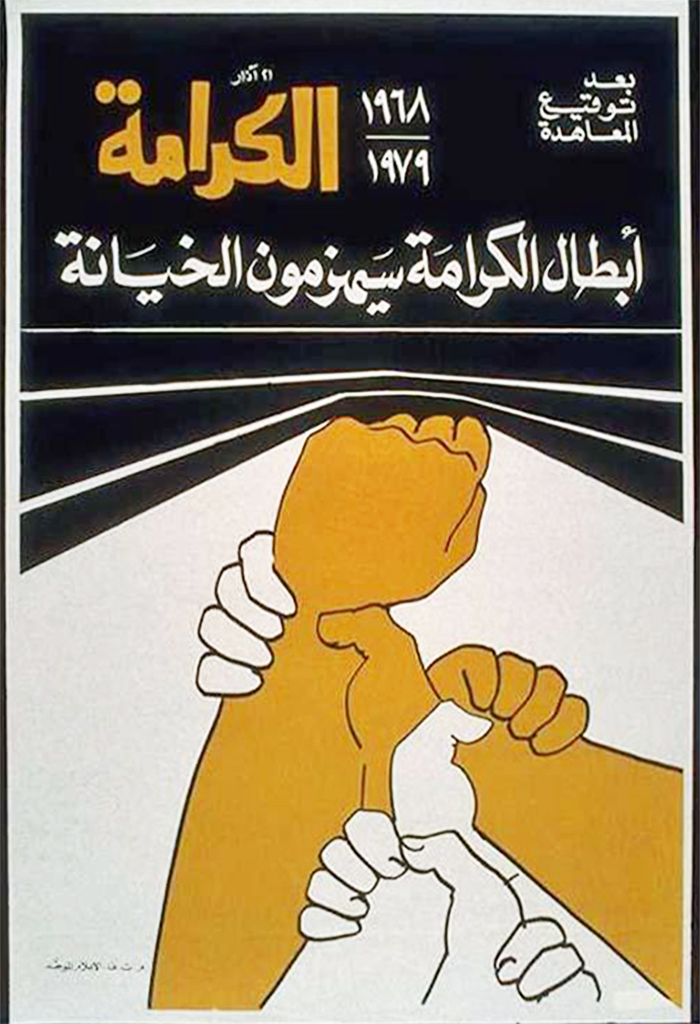

The establishment of the PLO in 1964 transformed the nature of popular mobilisation. In established states, official structures do not usually mobilise their public, except in emergencies such as war or natural disasters. However, popular mobilisation was an essential feature of national anti-colonial movements, and this kind of political action was practiced widely by the PLO, the Algerian FLN, the ANC, SWAPO, and across Latin America and Asia. This essential organisational practice is captured by the PLO’s motto of ‘patriotic unity, national mobilisation, liberation’. It signified the belief, expressed in the declaration of the establishment of the PLO, that unity and mobilisation opened the road to liberation and the restoration of the people’s rights. Notably, the PLO’s national charter of 1964 emphasised the need to mobilise the resources of the Arab nation as a whole for the successful liberation of Palestine.

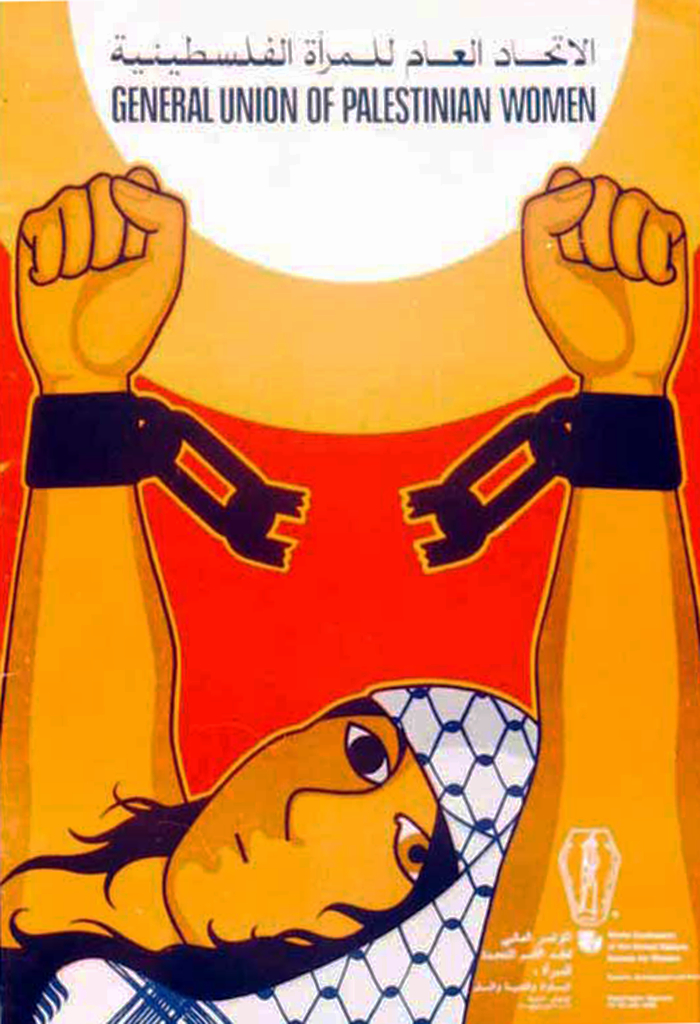

Mobilisation took many different forms in order to bring together the energies of all sectors of the Palestinian people. On the civic side, each of the popular organisations that were connected to the PLO played a distinct role. For instance, GUPW mobilised Palestinian women, the union of Palestinian workers was seen as a mobilisational arm for Palestinian workers, while the various teachers’ unions drew out their sector simultaneously across the region. This type of endeavour was often was carried out in tandem with the work undertaken by revolutionary movements and parties. For instance, students mobilised through GUPS were also often active in one of the major political parties or movements.

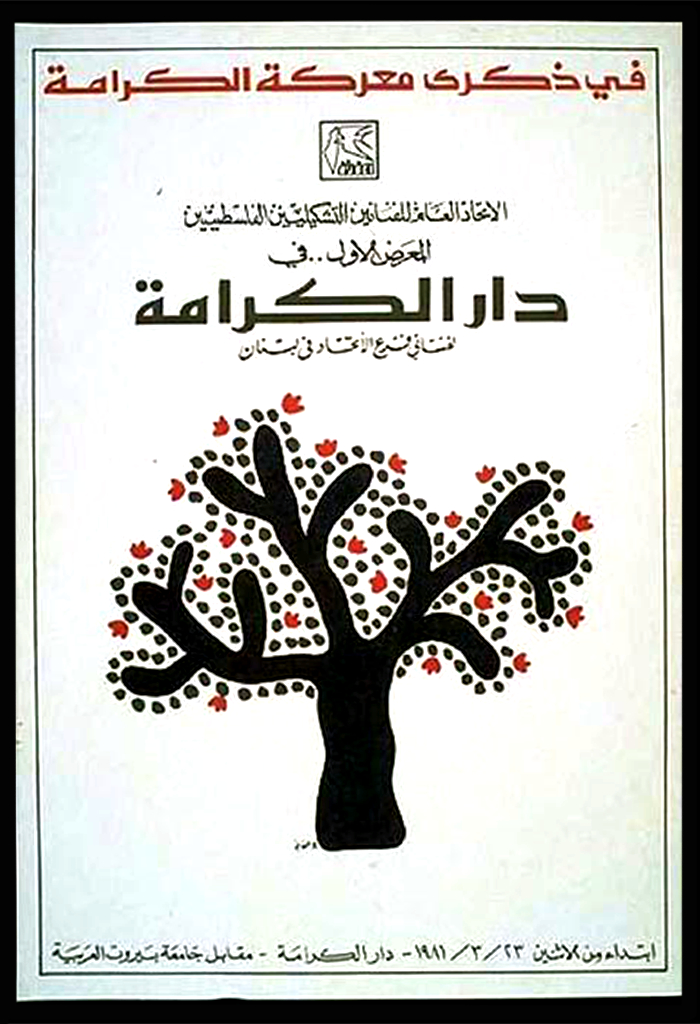

Movements themselves carried out a mass mobilisational role that transcended their own immediate environment. This involved careful and time-consuming work in every Palestinian refugee camp and major gathering of Palestinians. Talented revolutionaries were entrusted with this role in local arenas, focusing on cadre building. It often involved merging social work with the cultivation of strong revolutionary sensibilities. A different form of mobilisation took place inside the military prisons, and was often focused around the build-up of hunger strikes.

There was also military activity, including fida’i mobilisation, which channeled the energies of young Palestinians into irregular commando units run by the various parties and movements. More formal military mobilisation was experienced through joining regular units of the PLO’s Palestine Liberation Army.

Resource mobilisation was also extremely important. It was carried out by PLO financial organs such as the Palestine National Fund by a variety of means including the collection of taxes from Palestinian expatriates, the receipt of grants and loans from friendly states, as well as investments in various African and Asian countries. On a more grassroots level, Palestinian movements or parties often mobilised resources through member contributions, appeals to wealthy local figures, or fundraising by solidarity committees established in the Arab World.

These practices were typically carried out in parallel with vibrant and lively theoretical discussions on the subject. Every major Palestinian group and movement produced an extensive literature on comparative forms of mobilisation, their methods, functions and purposes. These materials were included in the internal education curricula for cadres.