Faced with the immediate task of overcoming their country’s recent destruction, there were pressing reasons for Palestinians to join the revolution, and a number of ways of doing so. Location, background, and circumstance played a major role in determining when and where cadres could join. When an ordinary cadre, Abu Sa'ado, sought to contribute to the armed struggle in 1968, he was moved by the oppression and dispossession he was then sharing with tens of thousands Palestinian refugees in Lebanon. For him, joining meant smuggling himself into Jordan, where the Palestinian revolution had its strongest presence at the time.

In 1971, a young woman born and raised in Haifa like Therese Halasa would have a different experience. By then, the revolution had largely moved from Jordan to Lebanon. Therese was raised in a politicised household, constantly listening to revolutionary ideas on the radio, and becoming involved in local activities. Living under the Israeli state, joining the revolution meant crossing secretly to Lebanon and undergoing extensive vetting before being allowed into the movement.

Cadres like Abu Sa'ado and Therese joined after the 1967 war, when the revolution operated above ground. However during the previous underground years the situation was much different. The clandestine movements had to be careful about protecting their members from arrest and torture, and having their plans broken up as a result of infiltration. Aspiring revolutionaries could only join after a rigorous process of recruitment that was often facilitated by relatives, friends, colleagues, or acquaintances.

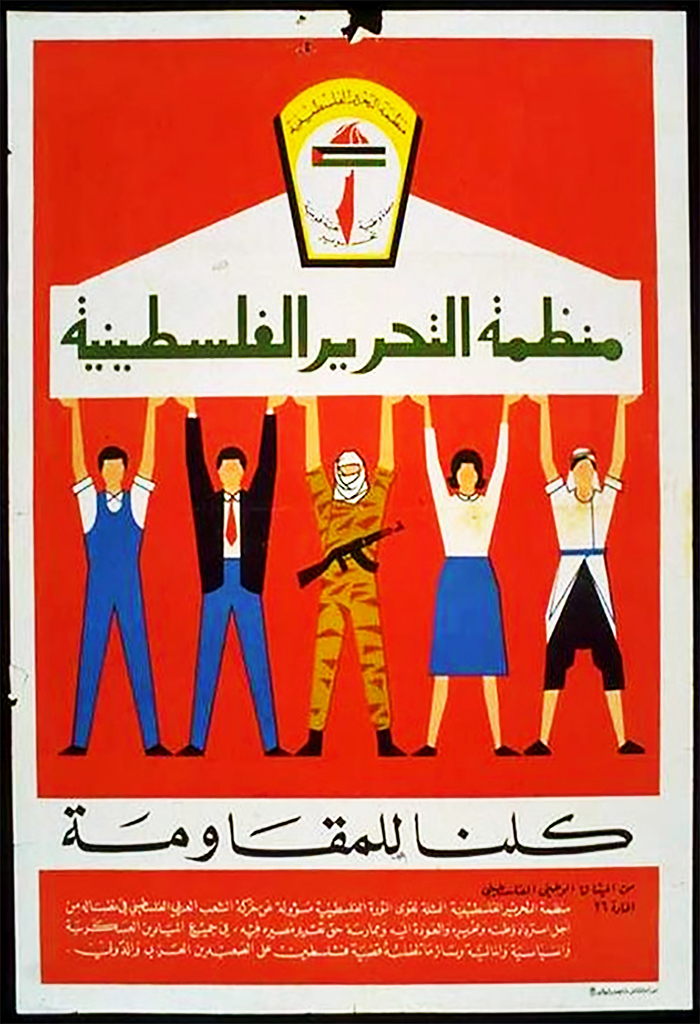

Another way of joining was to participate in popular organisations, such as student societies and unions, which were public and easy to access. Cadres belonging to different movements worked within these organisations, and enlisted new members from them regularly. It was common for a cadre to be active in his or her party while also participating in one or more popular organisations. In contrast, when moving from one political movement to another, members disposed of their older membership cards.

After 1964, another avenue for joining the struggle was the Palestine Liberation Army (PLA). This was a national institution formed by the PLO, recruiting openly with authorisation from the Arab League and host countries. The institution operated as a national rather than partisan body, and several PLA officers and soldiers ended up also joining specific political parties or movements.

Each movement had rules and rites when joining: for example, new members were usually required to recite an oath. Such initiation ceremonies were conducted and experienced in a variety of ways, but for most they were seen as a milestone, the expression of a declared attachment to – and identification with – the core principles of the movement they were joining.

Joining a revolutionary movement also meant receiving military training. To that end, special programmes were set up, ranging from improvised crash courses to specialised military courses.

Joining the revolution transformed cadres lives, bringing them into a world of new possibilities, where they could contribute to a collective endeavour in hundreds of different ways. Some joined already possessing developed skills and previous experience, so those specialising in academia, medicine or law, for example, often ended up at the Research Centre, the Red Crescent, or the revolutionary judiciary.

Cadres were not constrained by previous training and experience before joining. Many medics, such as Dr Yusri from Egypt, acquired political as well as clinical responsibilities when they joined. Those with military experience almost always ended up in the fida’i units or in the Palestine Liberation Army. Some joined after previously serving in Arab armies, and these included senior ranking officers, such as the leading Palestinian commander after 1970, Sa’ad Sayel (Abu al-Walid).

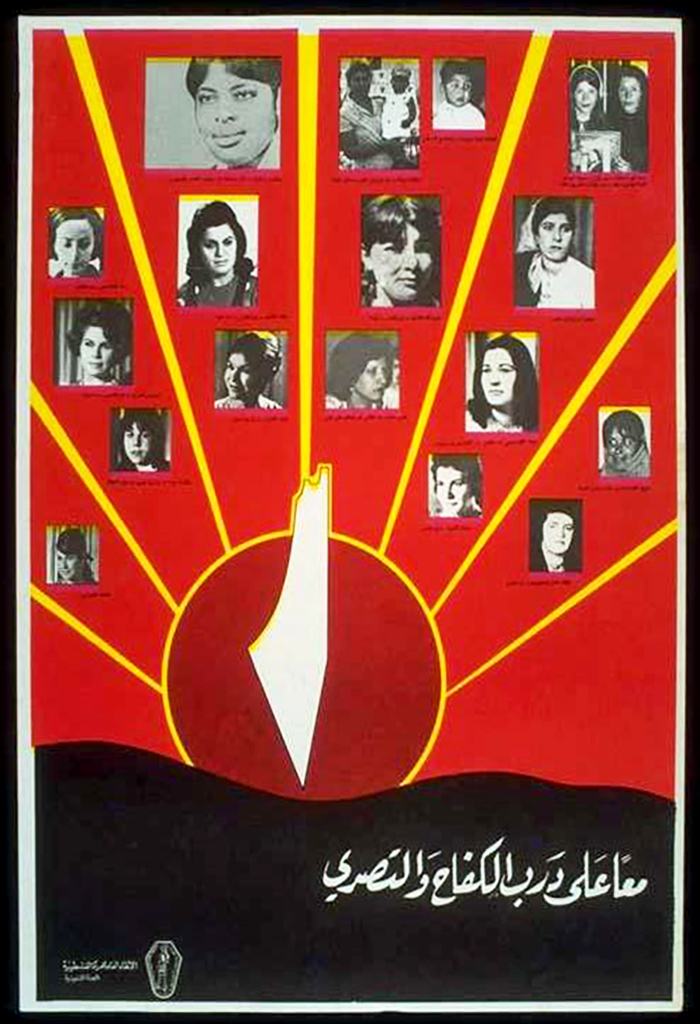

Most Palestinians joined at a young age, and acquired new skills after enlisting in the ranks of the revolution. There were a number of scholarship programmes that were established in tricontinental and Non-Aligned countries, such as India and Cuba, as well as the countries of the Eastern Bloc. These scholarships enabled young people to study medicine, engineering, the sciences, the humanities, and the military. Some graduates ended up in the military wing of movements, while others worked in the civil structures of the PLO. Many ended up serving in multiple levels and arenas. Aminah Jibreel, for instance, joined as a high school student working in a variety of spheres, ranging from organising demonstrations to digging trenches for fida’is in the South of Lebanon. She eventually settled in the General Union of Palestine Women, as a full-time union cadre.

Joining gave cadres both rights and responsibilities, which found their theoretical articulation in a range of revolutionary pamphlets. What it meant to be a virtuous cadre was the subject of regular debate and discussion, informed by reflections and practices from other global revolutionary experiences.