The expulsion of the Palestinian people from their country from 1947-49 was accompanied by an erasure of their political movements, national representation, and popular institutions. Young Palestinians sought to build structures in order to fill this political vacuum, as the founding document of Fateh, Our Manifesto highlights.

New political organisations were urgently needed which directly addressed the altered reality of Palestinian life, which was now characterised by dispersal, statelessness, and lack of representation. Given the sudden fragmentation of an entire people across several different countries, these structures were exceptionally diverse in terms of regional background, class, and gender. As a refugee people, Palestinians now mixed more: in tented refugee camps such as Karameh, young Palestinians from cities and rural villages lived intimately with each other, and formed close bonds, joining in the constant discussions on how to confront their new and harsh predicament.

The new political movements most typically began around a core group that worked in a similar political space and gradually developed a joint vision. As common spaces where young people met on a daily basis, high schools and universities gave rise to many such movements. The two largest, and most enduring, formed in Cairo and Beirut, where many young Palestinians were at university, both during and just after the Nakba. The Movement of Arab Nationalists started as a student circle at the American University of Beirut. The founders of Fateh were active in the Palestinian Students Association in Cairo as well as student gatherings in various other Arab locales.

Popular protests calling for anticolonial and revolutionary change, most often student-led, filled the Arab world throughout the 1950s, and played a central role in founding new political movements. Heavy state repression, as in the 1954 student protests in Beirut led to the deepening of common bonds and ideas, as well as further development of clandestine leadership structures.

Founding a movement often involved the fusion of already existing groups, as can be illustrated with the case of Fateh. Its first meeting, held in Kuwait, brought together former youth and student organisers from Cairo, Gaza, and Damascus. This was a first step towards including groups from surrounding countries in the Gulf and beyond.

Some groups were founded in a response to specific events. The Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine, for example, was created as a direct outcome of the 1967 war, and the subsequent decision of the Movement of Arab Nationalists to dissolve itself into several Arab movements operating independently.

Naming a group was an important act. Founders strove to use names with distinct ideological and organisational orientations, while appealing to the largest audience possible. Most groups were named a few years after they were established. The Movement of Arab Nationalists, for example, publicly used its name for the first time in 1958, several years after it began operating. This name was confirmed in 1959 after a survey of members was conducted.

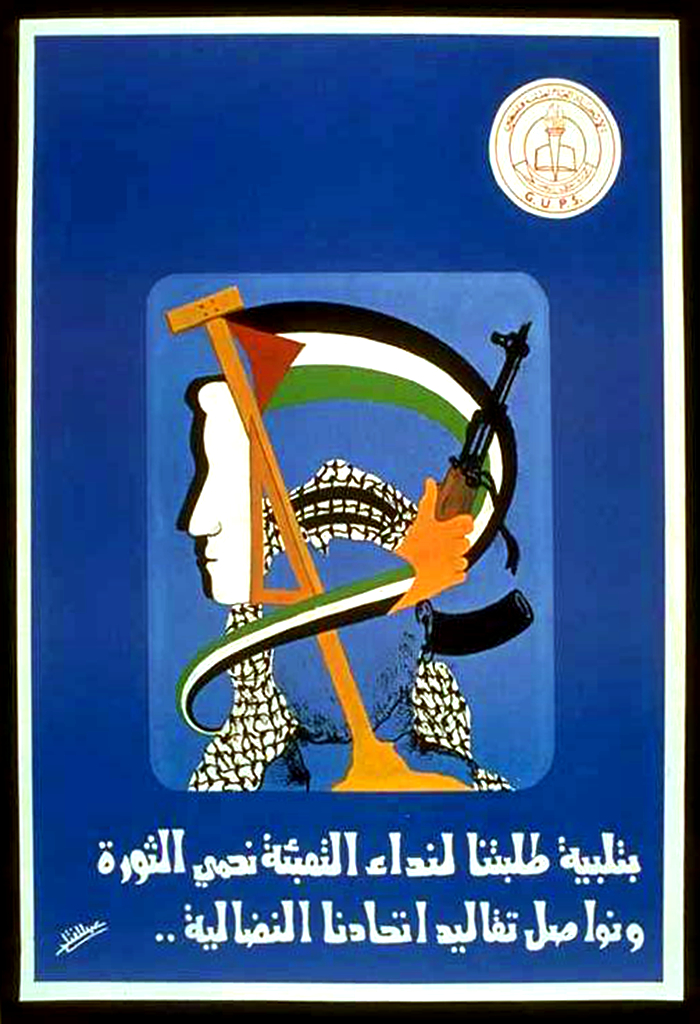

Symbols also played an important part in founding Palestinian structures. They cultivated a sense of internal cohesion and loyalty, and reflected the identity of the structure they represented. When the prominent Syrian artist Natheer Naba’a drew Fateh’s Al-Asifah symbol in 1966, he created symbols that were in tune with Fateh’s strategy at the time. The two intersecting arms covered with the Palestinian flag and carrying weapons captured at once the movement’s commitment to armed liberation, the need for Palestinian self-dependence, as well as the idea of unity in struggle. A full-blown map of historic Palestine was included to underscore the aim of liberating the land in its entirety. The inclusion of the three different individual weapons (a grenade, a sword, and a rifle), the flames, and the fiery calligraphy communicated the idea of guerrilla warfare. Naba’a created a highly dynamic effect through the intentional force of these combinations, with these symbols appearing to burst out of the frame.

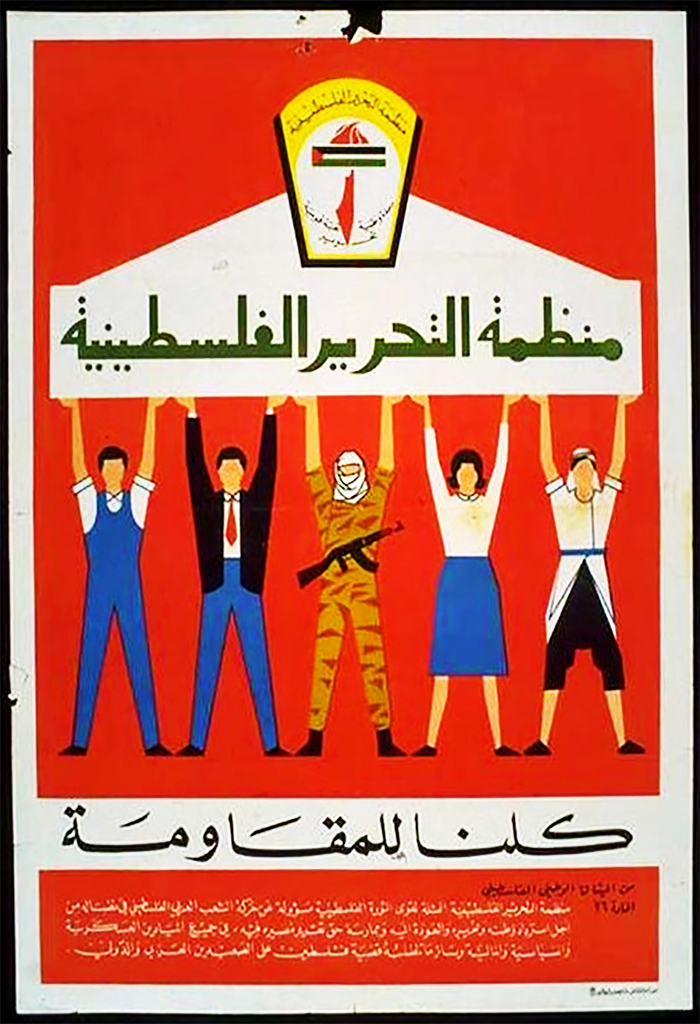

In contrast, when the Palestinian artist Ismail Shamout designed the PLO crest in 1964, he created a very sober effect that was commensurate with the PLO’s status as an overarching national structure, as opposed to an ideological or partisan one. Accordingly, he included just three unifying symbols- a full map of historic Palestine, the Palestinian flag, and a torch. These images respectively signify the homeland, the people, and freedom. Accompanying them was the motto of the PLO: ‘Patriotic unity, Arab national mobilisation, Liberation’.

As a national organisation, the PLO differed from Palestinian political and ideolgical movements in the nature and tone of its symbols. Founding a national structure had its own set of challenges: there was a need to be inclusive of the many Palestinian movements and sectors, and it was also essential to achieve recognition from the Arab states, so as to counterbalance their competing agendas and interests.

Founding the PLO required the creation of military, economic, diplomatic, cultural and social bodies representing a people in exile. Funds were needed to support these structures. Given these were secured directly from the Arab states or by fundraising within their boundaries, a longstanding dilemma of PLO revolutionary politics was to ensure that resources could be mobilised without undermining Palestinian independence. Developing independent Palestinian financial capacities was the rationale for the creation of such institutions as the Palestine National Fund.

Throughout the 1960s and 1970s, the PLO founded new bodies and structures, and thousands of Palestinian economists, social scientists, engineers, doctors and other professionals worked in them. Besides fulfilling basic needs, these national structures also contributed to unifying the Palestinian people, linking them in a multitude of material and affective ways.

Beyond national structures and clandestine movements, Palestinians also founded popular unions such as the General Union of Palestine Workers. Because of the broad dispersal of the Palestinian people, founding such popular structures depended on effective mobilising on national levels, but with local initiatives in each host country.

Two of the largest popular organisations, the students’ and the workers’ unions, were established before the PLO was founded, while other large unions, such as the General Union of Palestinian Women, founded in 1968, emerged under the auspices of the PLO. These unions in turn founded many sub-structures, such as the Bayt Atfal al-Summoud.

Popular organisations came to play an increasingly important role in the national politics of the movement, and were accordingly allocated a large percentage of seats in the Palestine National Council (PNC), established in 1964 as the Palestinian people’s parliament-in-exile. From 1973 onwards, the founding of new popular structures was guided by the framework settled at the PNC’s eleventh session in Cairo.