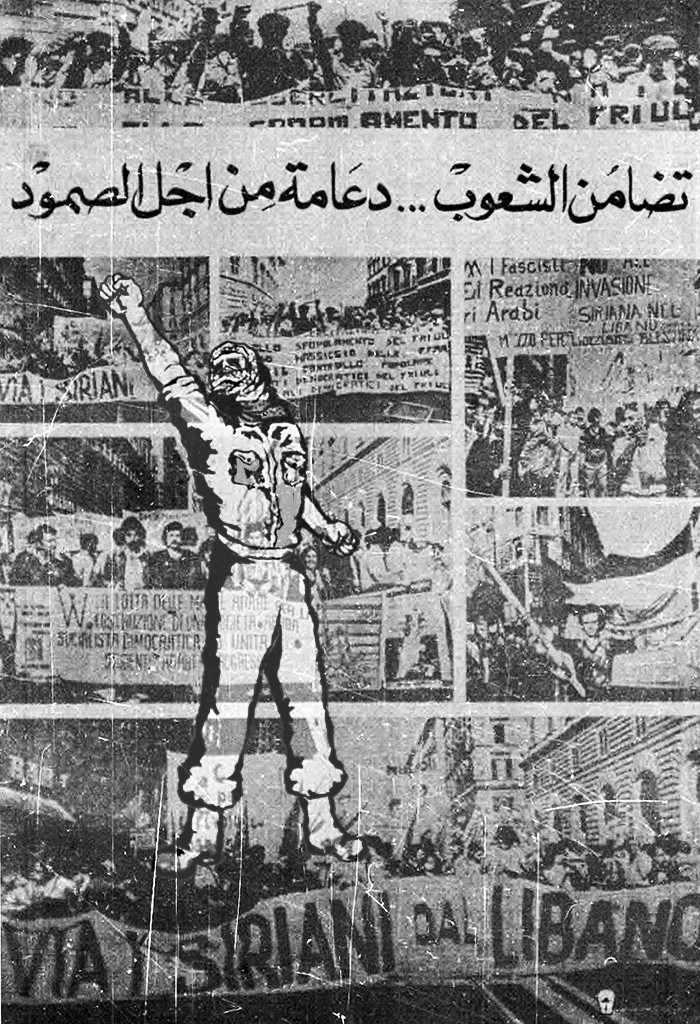

Palestinian revolutionary thought reflected an intense engagement with ideas and ideologies from other revolutions across the world, both past and present. In the 1960s Palestinian revolutionaries received strategic support from China, who developed their own powerful anti-colonial vision; in the 1950s, a decade earlier, the Arab Nationalist Youth found inspiration in the organizational model elaborated by China’s Liu Shaoqi’s revolutionary pamphlet How to be a Good Communist . Given the widespread sense of emergency after the Nakba, sources of revolutionary inspiration varied, and were widely sought, especially amongst young people. This led to the proliferation of numerous small groups throughout the 1950s and 1960s. Here, a group of young Palestinian refugees in Damascus, reading about the Carbonari (the clandestine Italian 19th century revolutionary movement) in their school textbook, were inspired to establish the secret group “The Arabs of Palestine”.

Palestinian revolutionaries commemorated and discussed international milestones of the larger revolutionary tradition, such as the centennial of the 1871 Paris Commune, while also celebrating their own historical struggle, especially the 1936–39 revolt. They were inspired, too, by recent radical popular models of struggle. The successful revolutions in Algeria, Vietnam, and Cuba were studied and regularly referred to. One important series published in the 1960s, Fateh’s Revolutionary Experiences and Studies, examined the histories of these armed struggles, and highlighted the factors that determined their success.

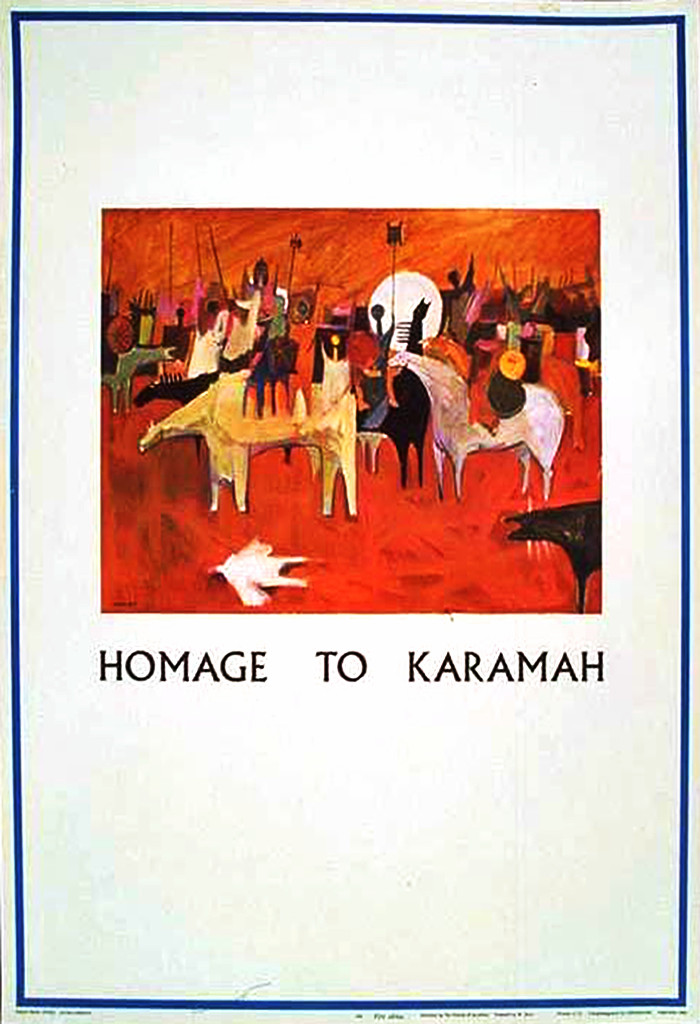

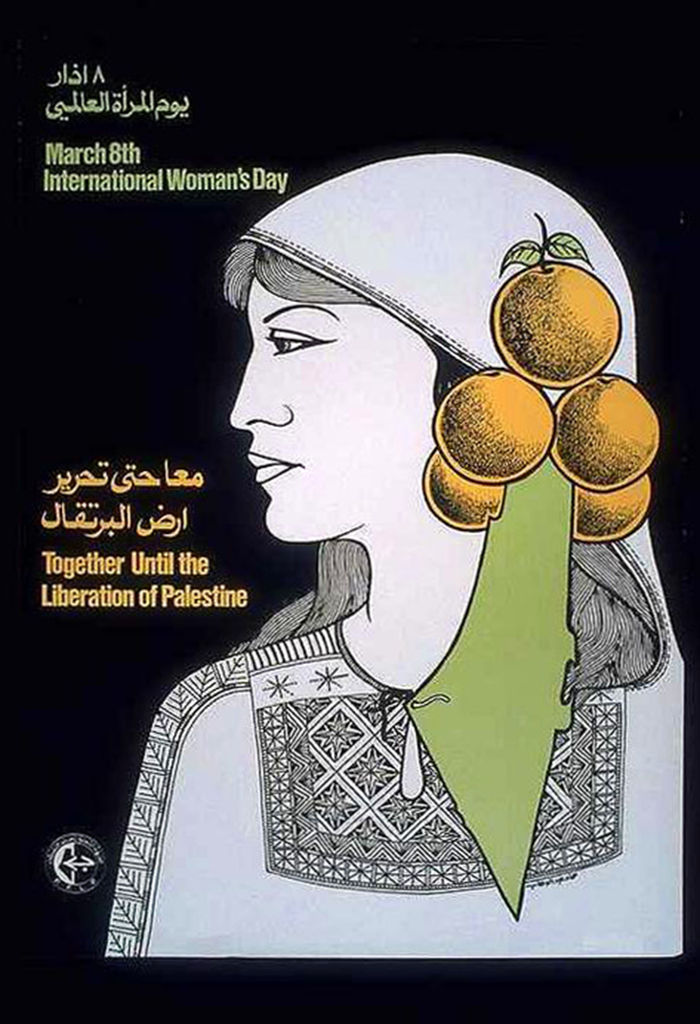

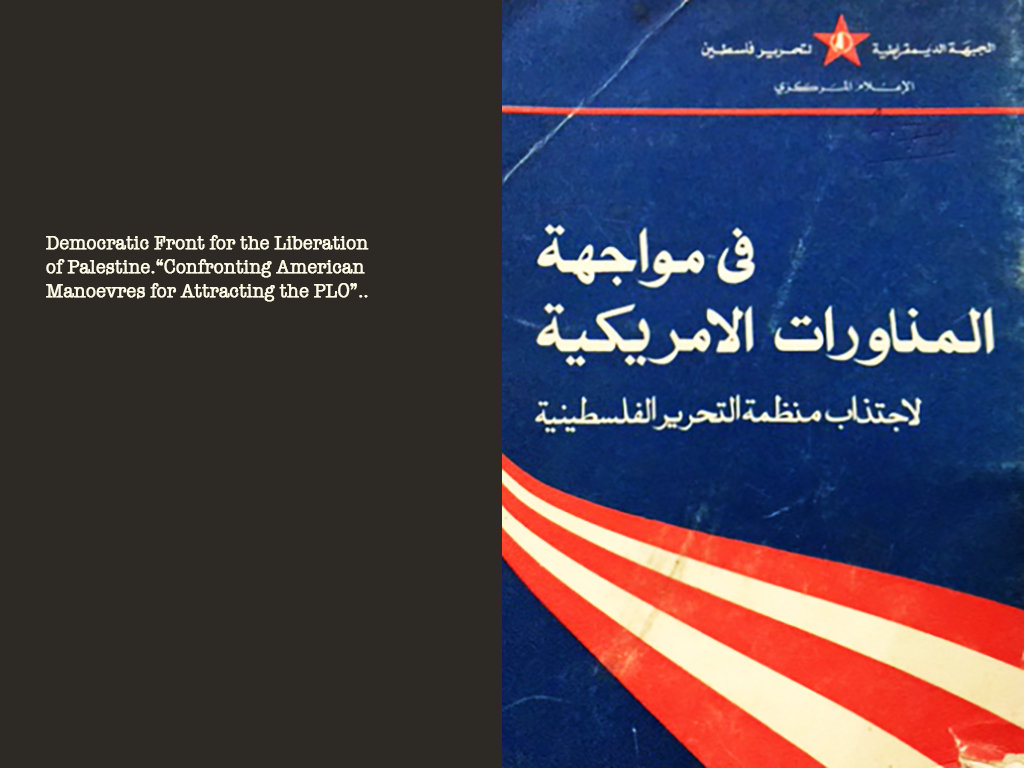

Palestinian revolutionaries developed and produced their own voluminous theoretical literature. In the 1950s, texts such as With Arab Nationalism, one of the most important Arab nationalist works of the decade, were widely read. In the 1960s, tracts appeared such as The Liberation of Occupied Countries, with its own vision of successful anti-colonial struggle. In the 1970s, essays such as Al-Hadaf’s Women and the Resistance addressed urgent social issues. Most of all, ideas emerged from an engagement with concrete struggles, and enshrined into revolutionary political programmes. Fateh’s 1968 single democratic state vision responded to the new political environment in the aftermath of the battle of Karameh. The DFLP’s famous “10 points programme” emerged directly out of the 1973 war.

Many of these debates were advanced by particular revolutionary movements and parties, but discussion was also taking place across the movements, especially within the PLO’s Palestine Research Centre. This institution trained a generation of Palestinian and Arab thinkers, including a large number of public intellectuals. They ranged from the Palestinian poet Mahmoud Darwish to the Lebanese novelist Elias Khoury, and the Syrian intellectuals Sadiq Jalal al-Azm and Burhan Ghalioun. Their studies appeared in the leading Arabic journal of the 1970s, Shu’un Filasteenya. The Research Centre organised meetings and roundtable discussions, during which the strategic and intellectual issues of the day were debated and explored.