The Palestinian revolution’s educational literature responded directly to the needs of a refugee people who were in the midst of an anti-colonial liberation struggle. The PLO Planning Centre developed curricula and other learning materials that were explicitly designed to fulfill the national education requirements of a new generation of Palestinian refugee children.

From the late 1960s, the Ashbal and Zahraat (Cubs and Flowers) scout movement flourished. This revolutionary scout initiative began in Karameh refugee camp and spread quickly to other Palestinian areas. These boys and girl scout groups met after school and during the summer holidays. A special scout magazine, Al-Ashbal, was produced by Fateh for young members, and Palestinian national and revolutionary themes were circulated in this way as well as through scout songs.

Palestinian children learnt of their history and their heritage through dance and performance art, and many of these groups toured internationally. In a revolutionary context, these artistic activities played a key mobilisation role, raising the morale of refugee children, and instilling among them a sense of dignity and rootedness.

Creative educational initiatives largely took place in local refugee camps. At the Baq’aa refugee camp in Jordan, for example, parties worked together with leading artists to introduce art education into the camp. Some initiatives were published, providing a creative outlet for children. These publications also generated local and international solidarity, by sharing their world with audiences who were unfamiliar with life in the refugee camps.

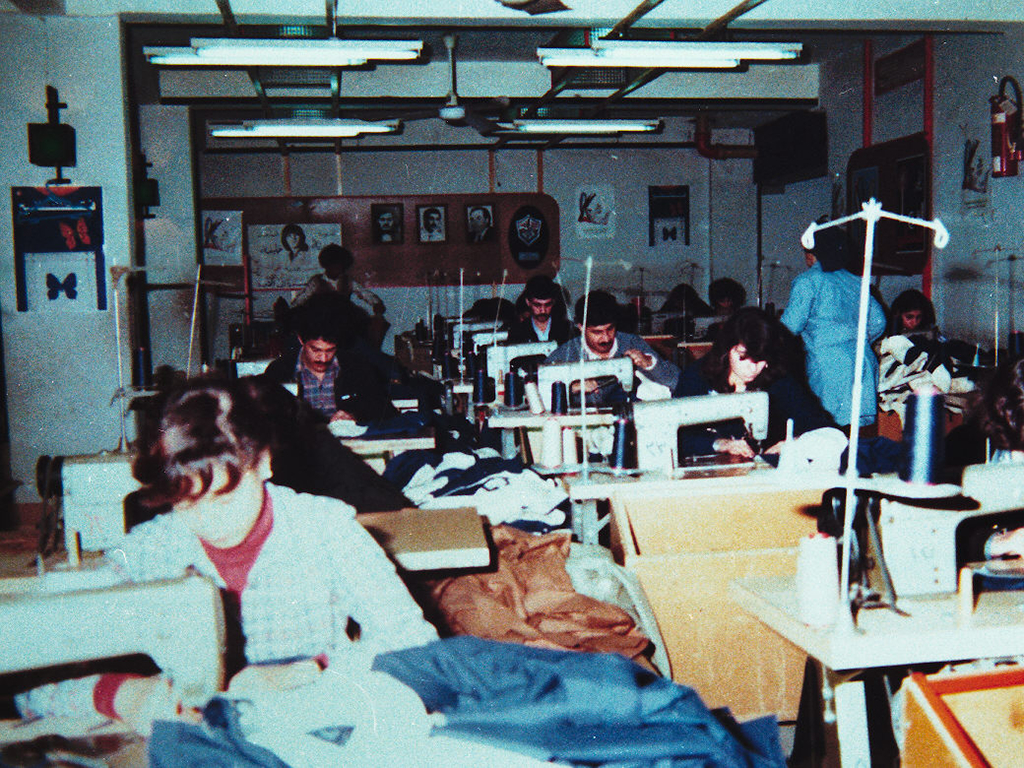

Technical education was also introduced for the families of martyrs, to ensure self-sufficiency in the camps, largely carried out by SAMED, a Palestinian production institution of the PLO that was formed in 1969.

Education took place beyond the classroom, through poster art and graffiti, and the walls of every refugee camp and Palestinian neighborhoods were blackboards on which the vocabulary of the revolution was inscribed. This allowed for mass circulation of the central ideas of liberation, and resistance to dispossession, while also sustaining the broader culture of return which was deeply ingrained in the Palestinian collective spirit (thaqafat al-awda).

Education included materials for youth of more advanced years, and every Palestinian political movement developed its own programmes of cadre education. Members read a variety of texts reflecting the ideological orientation of their party, and often discussed their readings in weekly cell meetings. From the 1950s, summer camps were organized for cadres, allowing them to develop ideological and practical skills, receive combat and resistance training, and meet other Arab and Palestinian members of their movement for the first time.

Special pamphlets introduced cadres to organizational principles as well as revolutionary behavioral codes such as critique and auto-critique.

By the 1970s, Fateh and the PFLP set up advanced cadre schools, offering courses on revolutionary theory and a variety of political topics. Expert lecturers taught in such programmes, with graduating classes addressed by party leaders.

Inside the Occupied Palestinian Territories, much revolutionary education took place inside the prisons of the military occupation, and each movement had its own highly developed educational programme and curriculum. Handwritten reproductions of revolutionary texts were studied and discussed in special reading groups. These materials were also widely circulated between the different movements, so a great amount of open debate and discussion took place within the closed prison environment.